THE

FIELDEN TRAIL

SECTION 2

Waterside via Wet Shaw, Todmorden Edge,

Edge End and Dobroyd Castle

If you are starting here you will have to get the Burnley bus out of Todmorden and get off at the Cornholme boundary sign. Otherwise from the end of Frieldhurst Road turn left down the A646 in the direction of Todmorden, keeping to the left hand side of the road. Just before reaching Dundee Road a seat is encountered in an alcove and a bus stop (no. 30) just inside the Cornholme boundary sign. Cross to the bus stop. This is where to get off if you are starting from Section 2. Between the stop and a small green area to the left, planted with half standards, a track leads up the hillside, following a zigzag route which eventually leads to the derelict farmhouse at Roundfield. Hartley Royd can now be seen on the other side of the valley.

Beyond Roundfield, the route continues and after avoiding a bad area of bog, arrives at another ruined farmhouse. Here a distinct track becomes a gravelly farm road, leading to Wet Shaw, which has just been rebuilt and hugs the hillside in the company of vans and rickety sheds. Continue onwards, following the farm road to New Towneley.

At New Towneley a choice must be made. If you continue onwards, following the track, you will arrive at West End, just beyond which you will be able to follow a descending track which will rejoin the main route above Flail Croft on its way to Todmorden Edge. This short cut will take time and effort off the journey, but will deny you the opportunity of seeing a spectacular bird's eye view of the Upper Calder Gorge and the imposing edifice of Robin Wood Mill, one of the Fieldens' many spinning mills. The Fielden Trail takes the latter option and heads towards the valley. Take the easy option if you like, but I'm going to Robin Wood Mill.

From New Towneley, follow an indistinct route down the pasture towards trees. Orchan

Rocks can be seen directly opposite, on the other side of the valley. Halfway down the

field the path is soon discovered on the left, running between a fence and a wall.

Only trouble is, there's no way of getting to it, when you arrive at the field corner you can see

the path leading out onto the crags, but you will have to climb over the fence to get to it. Once over the fence, turn right along the edge. just before the fence meets a wall, coming in from the right, a path may be seen descending the steep slope to the left, marked by a row of stakes. Follow this route down the hillside, and soon another path is met with, ascending from below left. This path comes up from Robin Wood Mill at Lydgate, which can be seen in the valley below.

Robin Wood Mill

This tall, grey edifice, nestling at the bottom of the valley, was once one of the Fieldens' spinning mills. Severely classical in design, it still manages to look imposing, despite broken windows and the fact that much of it now appears to be derelict.(AUTHORS NOTE. There was a fire not long after the Fielden Trail was published and now the mill is sadly reduced, much of it having been demolished!) What premises are still in use are the premises of The Todmorden Glass Co.

What a handsome building it is.(was!) A cotton mill, yes, but quite unlike the Mons Mill further down the valley, which is more typical of a later generation of Lancashire cotton mills, those red brick giants which dominate the landscape around Rochdale, Bury, Oldham and Manchester. Nearby is Fielden View and Robinwood Terrace, a uniform group of houses built in 1864 to house some of the Fieldens' workers perhaps? Even now, in decay, the community is dominated by the mill and the adjacent railway viaduct.

At this point perhaps we ought to take a look at the cotton industry, which made the Fieldens their fortunes and is therefore closely bound up with the subject of this book. The cotton industry was literally created by self made men like the Fieldens between the years 1770 and 1840 in a period of spectacular growth. It continued to expand, reaching its peak in 1912 when 8 million yards of cotton were produced. After this date increasing foreign competition along with various other factors were to bring about the gradual decline of the industry. By 1803 cotton had already overtaken wool as Britain's leading export, quite an achievement for an industry based entirely on imported raw materials. The reasons for this sudden boom are varied. The invention of the Saw Gin by Eli Whitney was certainly a contributory factor to cotton's phenomenal growth, for it opened up a supply of cotton from the Southern United States at a time when other sources, for example the West Indies, were beginning to prove inadequate. U.S. growers consistently reduced their prices up to 1898, and this enabled Lancashire to create an industry which was to make the whole world its market.

Why Lancashire? Basically because it had all the right qualifications: cheap land, coal, and soft water which was ideal for bleaching, dyeing and printing, not to mention the powering of machinery. In Liverpool, facing the Americas, 'King Cotton' was to find his port, and in Manchester his market. In Lancashire there were fewer restrictive practices like guilds and ancient corporations to hinder the development of the new industry. In many ways preindustrial Lancashire was rough, wild and poorly developed, but for the building of a cotton industry conditions were ideal, and, when it came, the growth was simply phenomenal.

The technology which made such a growth possible had been developing for some time. In 1733 the 'Flying Shuttle' devised by John Kay of Bury triggered off a whole pattern of invention which was to transform the whole social and economic structure of those northern regions involved in textile industries. In 1760 came Hargreaves' 'Spinning Jenny', and in the 1770's Arkwright's 'Water Frame'. 1779 saw the invention of Crompton's 'Spinning Mule' and 1785 Cartwright's Power Loom. The development of the steam engine by James Watt ensured the gradual changeover from waterwheels and goits (artificial watercourses) to boilers and mill engines, with subsequent changes in the priorities of mill siting. The demand for coal rather than water and the need for inlets and outlets of raw and finished materials were to bring improved communications in the form of canals, and later, railways. The spate of inventions continued throghout the 19th century: Radcliffe's Dressing Machine (1803) prepared threads for weaving; Dickinson's 'Blackburn Loom' (1828) introduced picking staves; The 'Self Regulating Mule'; 'Ring Spinning'; 'Northrop Looms'; the list goes on, and on, and on.

The production of cotton cloth did not only involve spinning and weaving. The cloth had to be 'finished' and dyed, and a whole series of inventions and processes evolved to improve this area of the industry. Early methods of finishing were costly and slow. This was particularly true of 'bleaching', which in the late 18th century required many acres of grassland for exposing cloth to sunlight and water (crofting). Another process, 'bowking', immersed the cloth in alkaline lyes concocted from the ashes of trees and various plants. Cloth was 'soured' in buttermilk and washed in 'becks' filled with running water, all complex and time consuming processes.

Then came the changes. In 1750 the use of dilute sulphuric acid reduced the time taken for souring by half. In 1785 the French chemist Berthollet devised a chloride of lime bleaching powder. New methods of mass producing bleacher's materials like soda ash,' caustic

soda and chlorine gas were also introduced in the 19th century. 1828 saw the introduction

of Bentley's 'Washing Machine'; and in 1845 Brook's Sunnyside Print Works in

Crawshawbooth used steam power to carry the ropes of cloth through all the stages of the bleaching process. 1860 saw the use of caustic soda by John Mercer of Clayton le Moors to produce a silken finish on the cloth, known as 'Mercerisation', and in 1856 Perkins succeeded in extracting mauve aniline dye from coal tar, which up to that time had been a waste product from the gasworks. Previous methods of dyeing had involved up to 19 different processes, including immersion in cow muck!

The impact of all this development upon Lancashire was immense. The whole region was transformed where King Cotton held sway. Cotton brought new mills, machinery, houses, canals and railways. New communities came into being. The development of Todmorden

The Fieldens' spinning mill at Robin Wood, Lydgate.

from a small hamlet into a substantial mill town was almost entirely due to the cotton trade. The mill owner and his operatives were but the tip of the iceberg, a host of interests were involved, from engineers, architects and builders, to chemists, bankers and financiers. Cotton created a demand for textile machinery, steam engines and boilers, houses, gas, electricity and transport. As a result of the cotton boom, Britain's best engineering skills were concentrated in and around Lancashire; and Merseyside's chemical industry owes its origin to cotton's consumption of dyestuffs, bleaching powders and soap. Mining, ironfounding and glassmaking also served the cotton industry. Indeed, it seemed that King Cotton was everyone's employer.

Prosperity and growth however, were not the only new developments at the court of King Cotton. There were other, less agreeable 'innovations' like bad housing and sanitation, grinding poverty, child labour, dangerous working conditions, and, most significantly of all, unbearably long hours. "Overwork," wrote Leon Faucher in 1884, "is a disease which Lancashire has inflicted upon England, and which England in turn has inflicted upon Europe."

It was in this context that the name of Fielden was to become universally esteemed, and to earn a fame far more enduring than that of mere charitable mill magnates, as we shall see. The Fieldens saw the benefits that might be derived from the factory system, but, unlike most of their class, they were painfully aware of the evils it created, and took steps not only towards easing the lot of the working man, but also towards his political emancipation, as we shall soon discover.

The next section of the Fielden Trail leads to Todmorden Edge. After meeting the path coming up from Robin Wood Mill, continue onwards and slightly upwards, contouring round the hillside. Soon there are good views down the valley towards Todmorden, with Centre Vale Park and the Mons spinning mill in the foreground.(AUTHORS NOTE Since demolished!) Mons is a much later mill than Fielden's at Robin Wood, and was built on The Holme, a large open space where fairs and circuses were formerly held. Opposite the remains of Royd House, which is now just a pile of stones overgrown with elder trees, join an ascending track in a gully (passing yet another ruin) which soon arrives at a rusty old gate facing West End on the hillside, to the right of another farm, Dike Green. Here the alternative route from New Towneley is met with. If anybody decided to miss Robin Wood Mill from the itinerary and take the short cut, they will be waiting for you here. Now turn left (you will have to climb over the wooden gate) and follow a green track past the head of Scaitcliffe Clough. At Flail Croft nearby, lived (in 1714) Samuel Fielden, brother of Nicholas of Edge End, and John of Todmorden Hall, both of whom we will encounter later. Continue onwards until a wall and wooden gate are joined (on left). Pass through this gate, and be careful when you shut it, as when I did so I was miles away in thought and did not see the eye level barbed wire which made a neat little cut on my forehead! Beyond a stone in the wall on which is carved the letters I M bear left across the fields to enter the lane leading to Todmorden Edge.

Todmorden Edge

If Nonconformism had shrines then Todmorden Edge would certainly be one of them, for it has associations with both the early Quakers and the early Methodists. Quaker meetings were held at Todmorden Edge Farm and, as at Shore, there is a 'Quaker Pasture'. Early Quakers were persecuted, and Todmorden Edge has seen its share of that. Henry Crabtree, who was curate of Todmorden in the 1680s, viewed the Friends with great distaste. With Simeon Smith, his servant, he surprised a number of Quakers from Walsden and Todmorden when met together at the house of Daniel Sutcliffe, at Rodhill Hey on May 3rd 1684. A fine of five shillings was imposed on each person present. As the fines were not paid, distraints were made on their goods. A month later, a meeting in Henry Kailey's house at Todmorden Edge was similarly disturbed and goods to the value of 20 pounds, an ark of oatmeal, and a pack of wool were taken.

Todmorden must have been noted for the number of Friends, for when those who declined to pay for repairs to the church and school at Rochdale were summoned by the Rochdale Churchwardens, it was stated that the majority of the offenders came from Todmorden, where Quakers were "both numerous and troublesome". Fortunately for the Fieldens and others of their faith 1689 saw the passing of the Toleration Act, which enabled Quakers to register their meeting houses officially for the first time.

In the wake of the Quakers came the Methodists. On 1st May 1747, John Wesley preached

at Shore at midday; then later, at Todmorden Edge Farm, he called "a serious people to

repent and believe in the Gospel". The following year, on October 18th 1748, the

first recorded quarterly meeting ever held in Methodism took place at Chapel House,

Todmorden Edge, under the chairmanship of that noted religious firebrand William

Grimshaw (who was curate of Todmorden before his more famous association with

Haworth). Methodism obtained many converts, and the Friend's Meeting House at Todmorden Edge, along with a Meeting House and a Baptist Chapel at Rodhill End, were sold to the Wesleyans.

The Fieldens, unlike many of their Quaker brethren, were not converted to Methodism. They remained Quakers, but for all that the Methodists were to play an important part in the establishment of Unitarianism in Todmorden, with which the Fieldens were actively

involved.

From Todmorden Edge the Fielden Trail moves on to Edge End, the home of Todmorden's first industrial entrepreneur, and father of 'Honest John' Fielden, Joshua Fielden of Edge End. As we leave Todmorden Edge with its Wesleyan associations it is perhaps worth bearing in mind that John Wesley, for all his goodness and unwavering faith, went so far as to recommend child labour as a "means of preventing youthful vice". John Fielden, who was born 36 years later in 1784, would hardly have agreed with such a sentiment.

On meeting the Calderdale Way by the stables at Todmorden Edge Farm, bear right, following the concreted farm road past a white gate to where it meets tarmac at Parkin Lane. From here the route continues without difficulty (following the Calderdale Way) to......

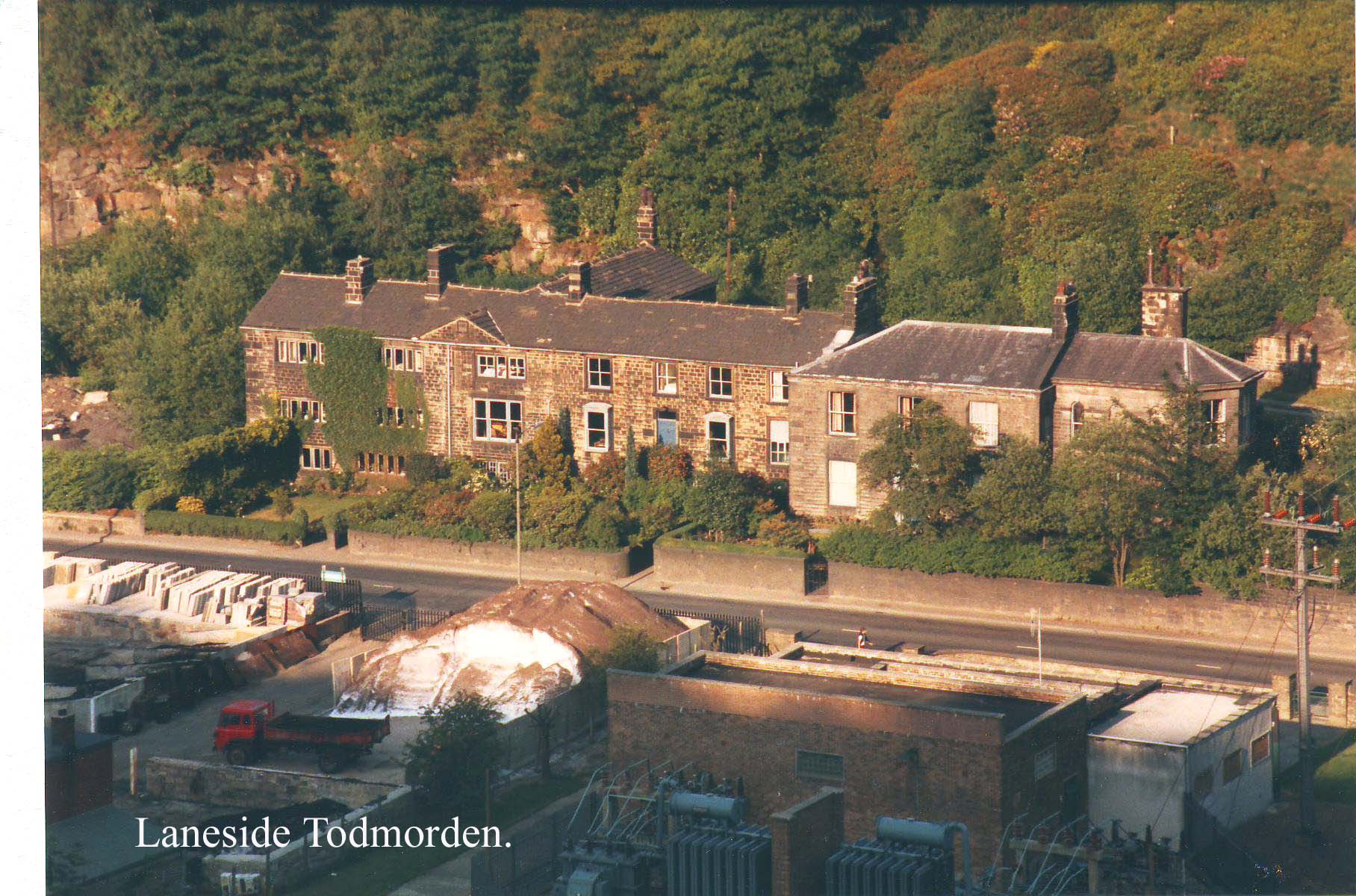

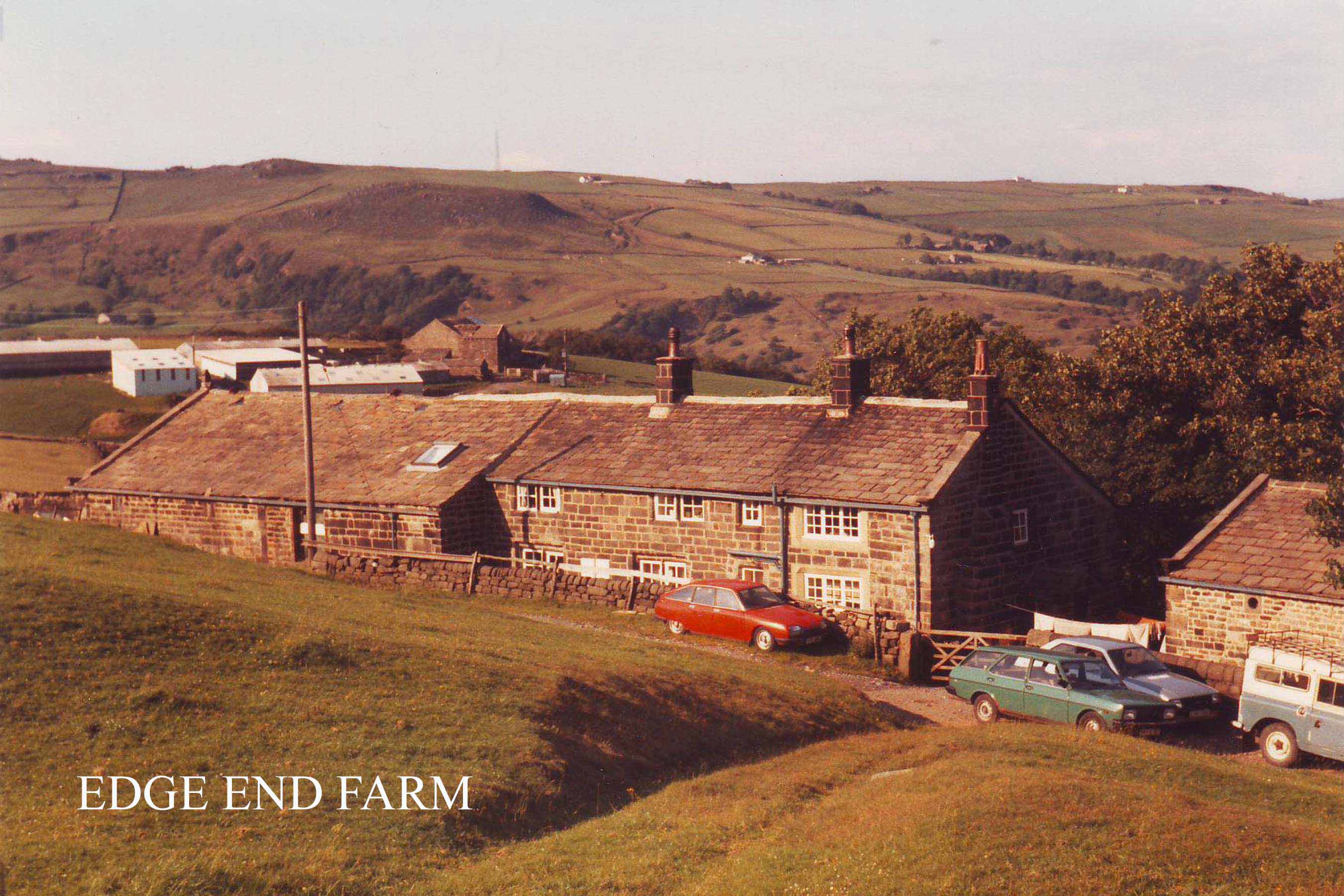

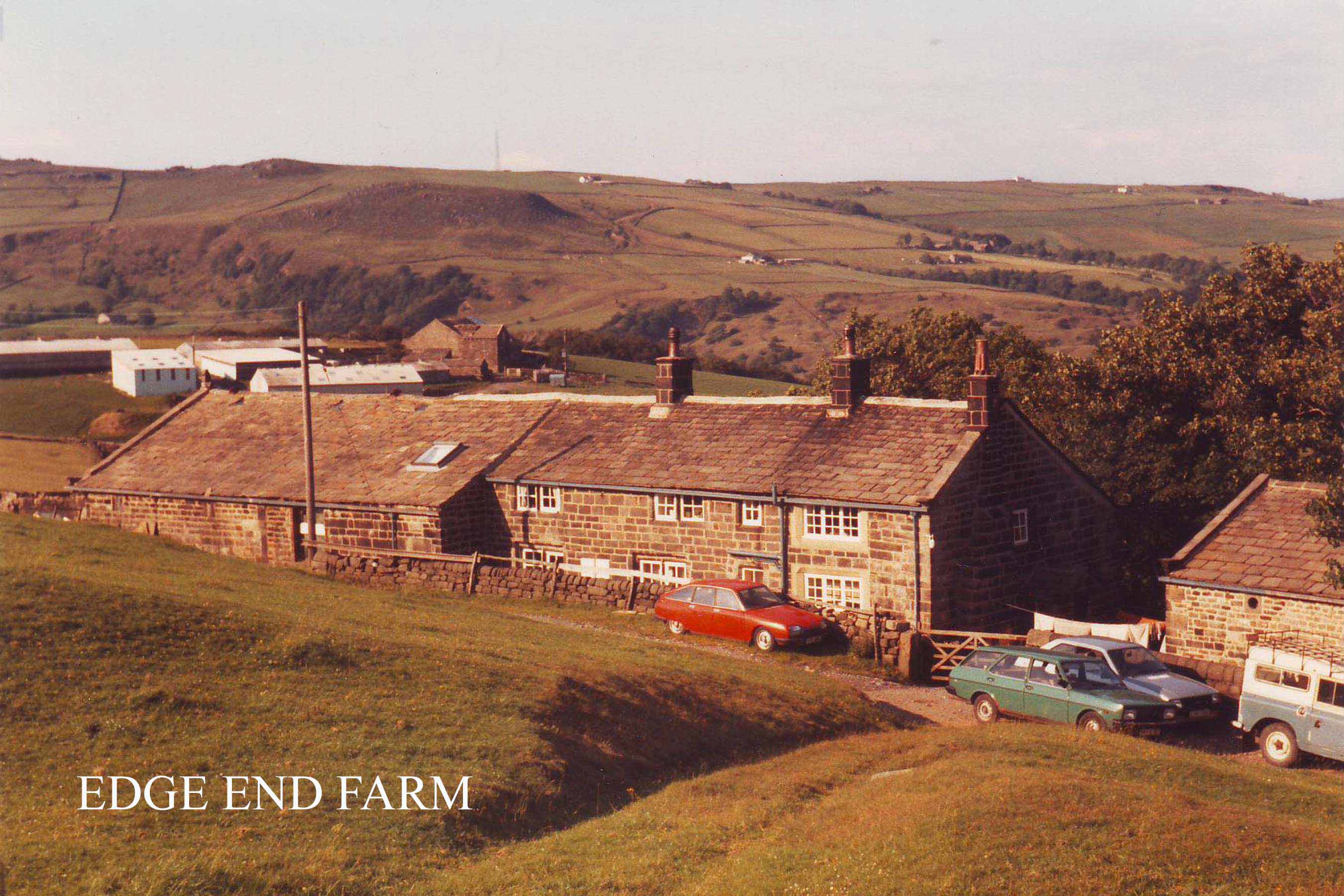

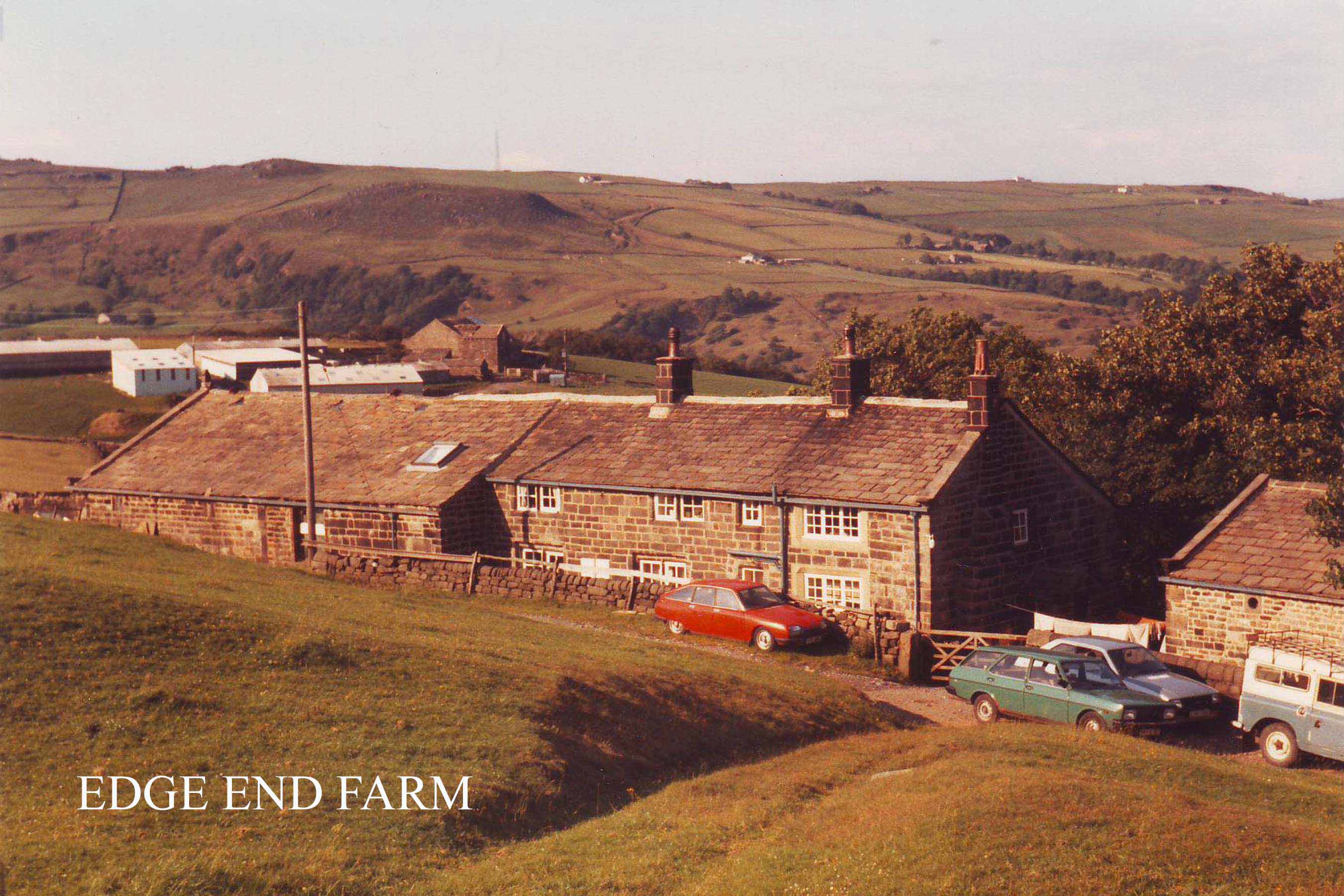

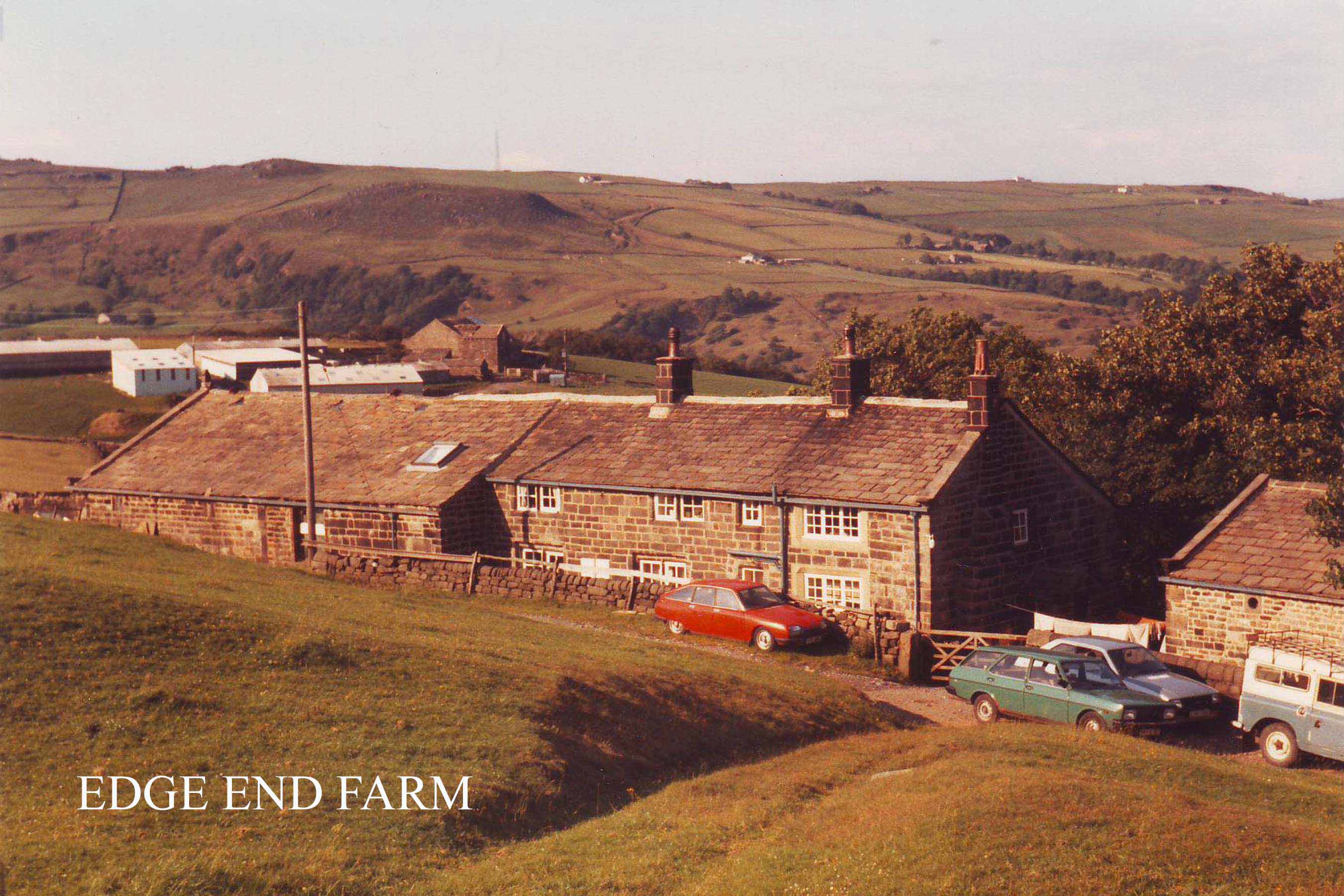

Edge End Farm

At Edge End we come to an important chapter in the Fielden story. Here is the scene of the Fielden's transition from farming and wool to industry and cotton. This low, embattled stone farmhouse hugging the hillside was where the Industrial Revolution in Todmorden was born. The initiator of the chain of events which was so greatly to transform the fortunes of both the Fieldens and those around them was Joshua Fielden, 'Honest John's' father. Joshua Fielden was not the first of that name, nor would he be the last. His second son was called Joshua, and he was to have a grandson and a great grandson of the same name. As if that was not confusing enough, we also find that his father, grandfather and great grandfather were also called Joshua! Because of this I have found it necessary to number all these 'Joshuas' in the hope of lending at least a little clarity to a confusing and misleading situation.

Back at Hartley Royd we discussed Abraham Fielden of Inchfield who married Elizabeth

Fielden of Bottomley in the early 17th century. Their third son, Joshua Fielden of

Bottomley, although not the first Fielden to bear that name, was certainly the first Joshua in his

line, so for that reason I have referred to him as Joshua (I). From him the Joshua Fieldens of Bottomley and Edge End run as follows:

JOSHUA FIELDEN (I) of Bottomley Quaker. Received Bottomley from brother John of Hartley Royd. Died 1693.

JOSHUA FIELDEN (II) of Bottomley. Died 27th February 1715.

JOSHUA FIELDEN (III) of Edge End. Born Bottomley. Died at Dobroyd. (1701....1781)

JOSHUA FIELDEN (IV) of Edge End and later Waterside.

(1748...1811).

From this we can see that 'Honest John's' father was the fourth successive Joshua in his line. Joshua Fielden (IV) was a Quaker like his forebears, and who lived in "a bleak, pious fashion" at Edge End Farm. His uncle Abraham (1704...1779) had inherited property at Todmorden Hall (this is a connection we will explore later) and was actively involved in the domestic textile industry. Joshua too, like most of the farmers around him, was involved in the production of woollen cloth, which was the traditional occupation of the whole district. By the mid 18th century the domestic system of cloth production had reached the height of its importance. Originally the farmer weaver simply produced his cloth at home and carried it to market (a cloth hall had been established as early as 1550 by the Waterhouse family of Shibden). Soon however, the business diversified and expanded: weavers collected into small settlements, the weaving hamlets linked by causeys and packhorse ways; while local merchants often acted as middlemen, selling raw wool to the weavers and buying back the finished cloth. As a result of this, in the 17th and early 18th centuries prosperous clothiers' houses began to appear, many of them with a "takkin' in shop" alongside. By the mid 17th century Halifax had its own cloth hall, but did not completely supersede the Heptonstall one until the Halifax Piece Hall was opened in 1779.

Joshua Fielden, like most farmerweavers in the Upper Calder Valley, had to work hard for his living. He attended Friends' weekly meetings at Shoebroad, farmed, wove his cloth and every weekend walked to the Halifax market and back with the cloth 'pieces' on his shoulders, a distance of 24 miles. Yet times were changing in the latter years of the 18th century. Maybe Joshua was getting a bad back and sore feet, or perhaps he simply had an eye for the main chance. Whatever his reasons, Fielden realised (in the words of J. T. Ward) that "Todmorden's geography permitted its embryonic industrialists to choose between cotton and wool." It was time to make that choice and Joshua chose cotton, a new material that perhaps offered more exciting prospects than the stolid, traditional pursuits of his forefathers.

Whatever his reasons may have been, Joshua Fielden turned his back on Halifax and was drawn westwards to the markets of Bolton and Manchester. It was time to break away from the established way of things.

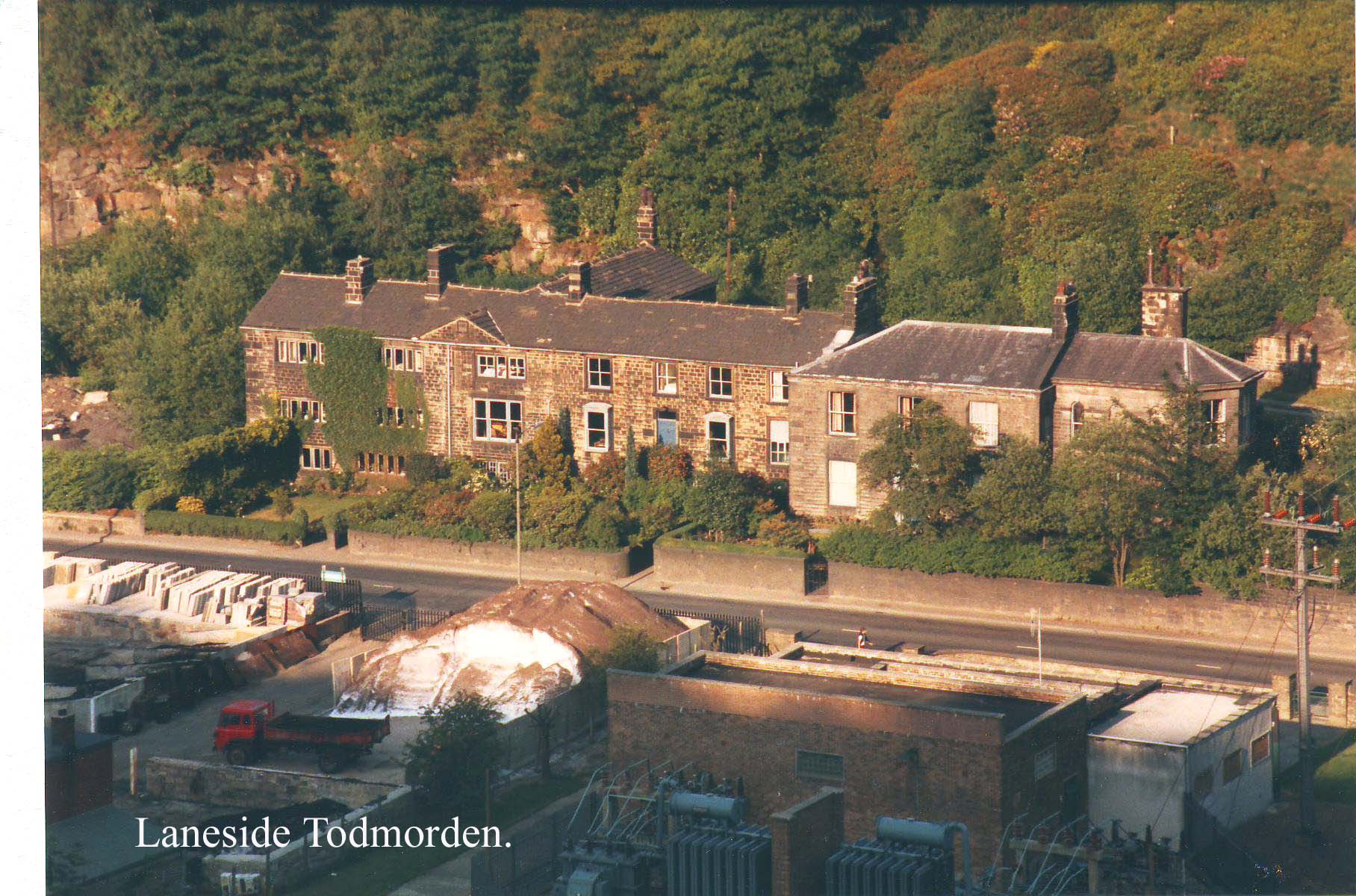

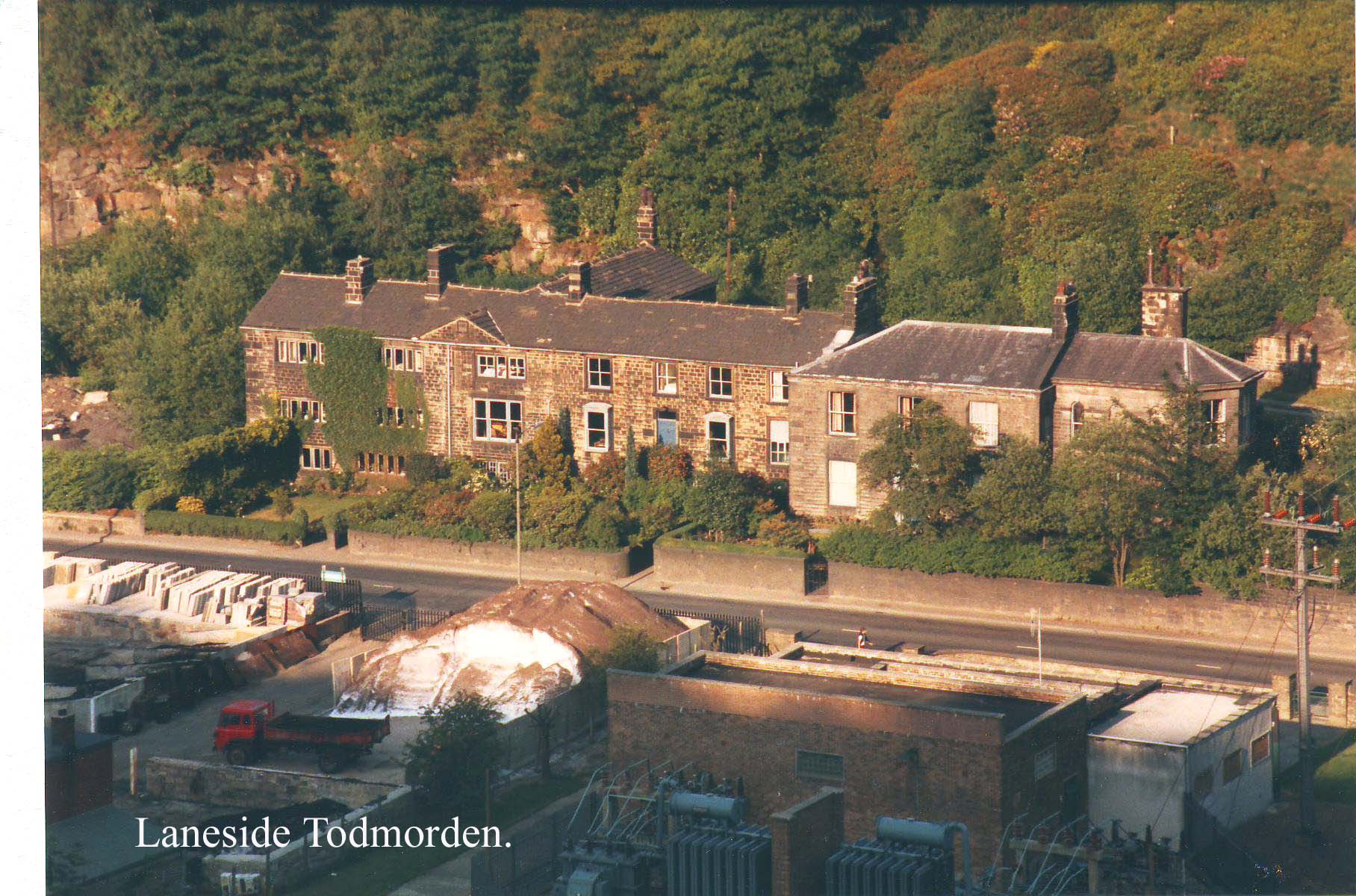

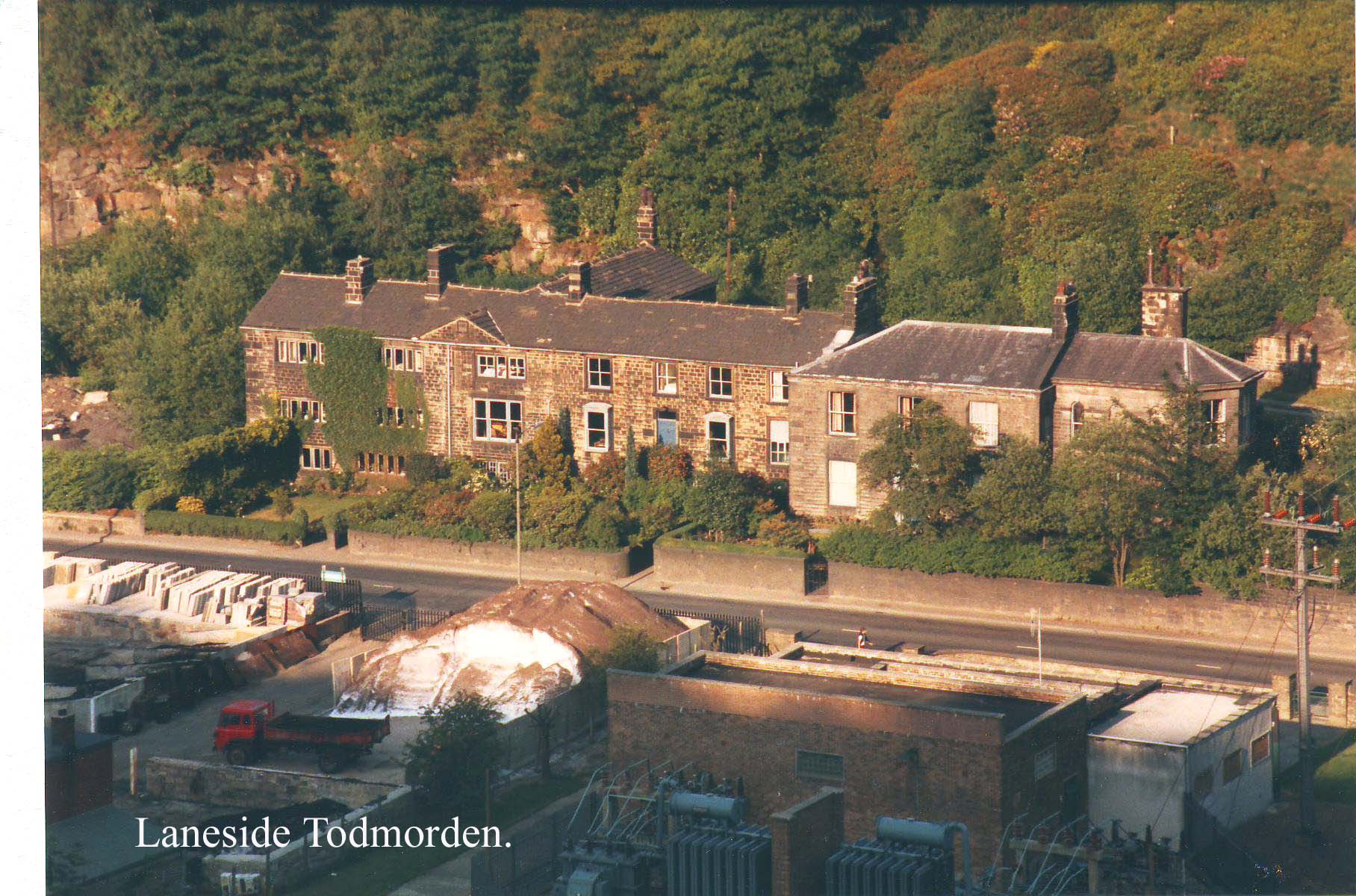

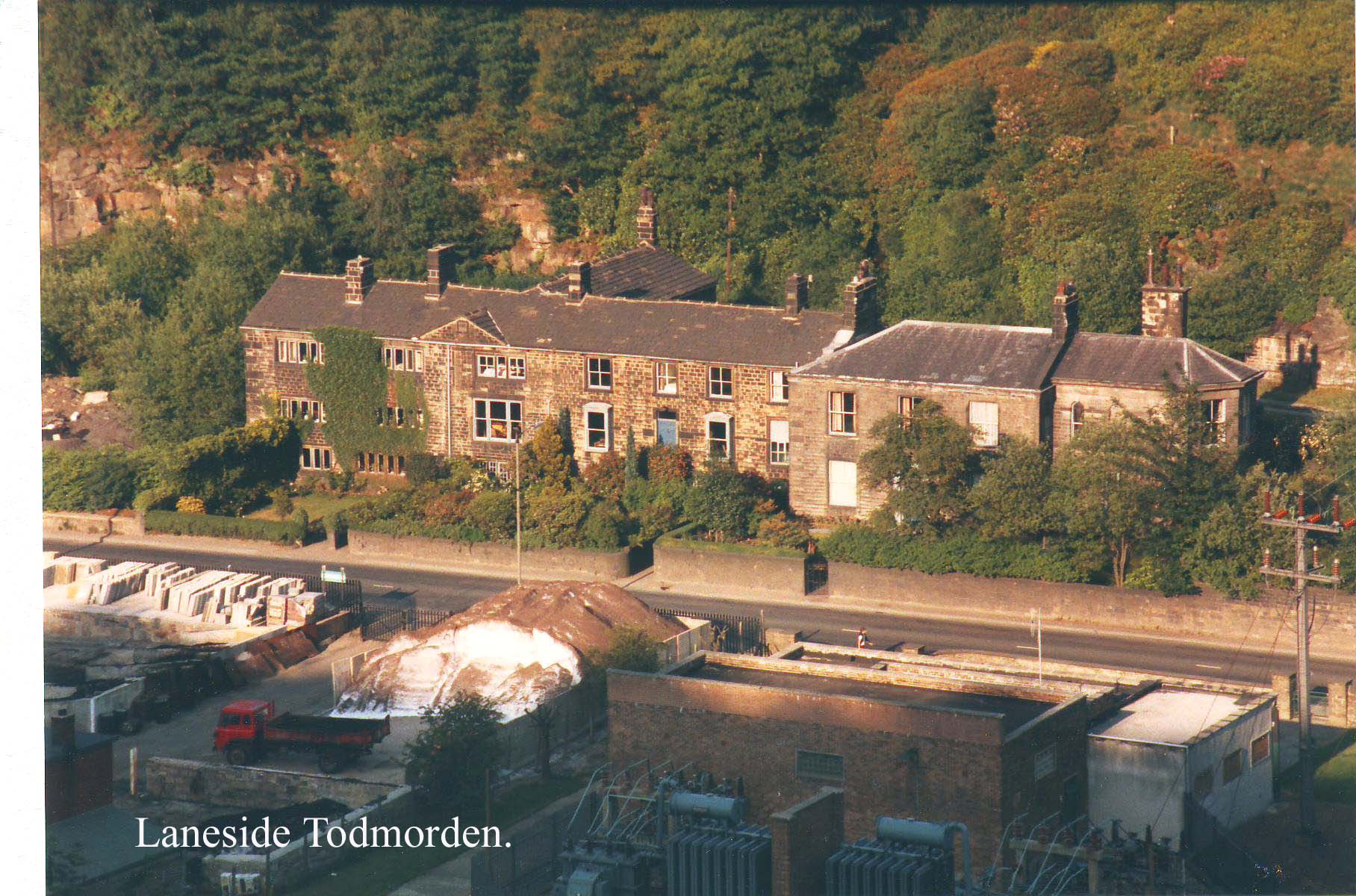

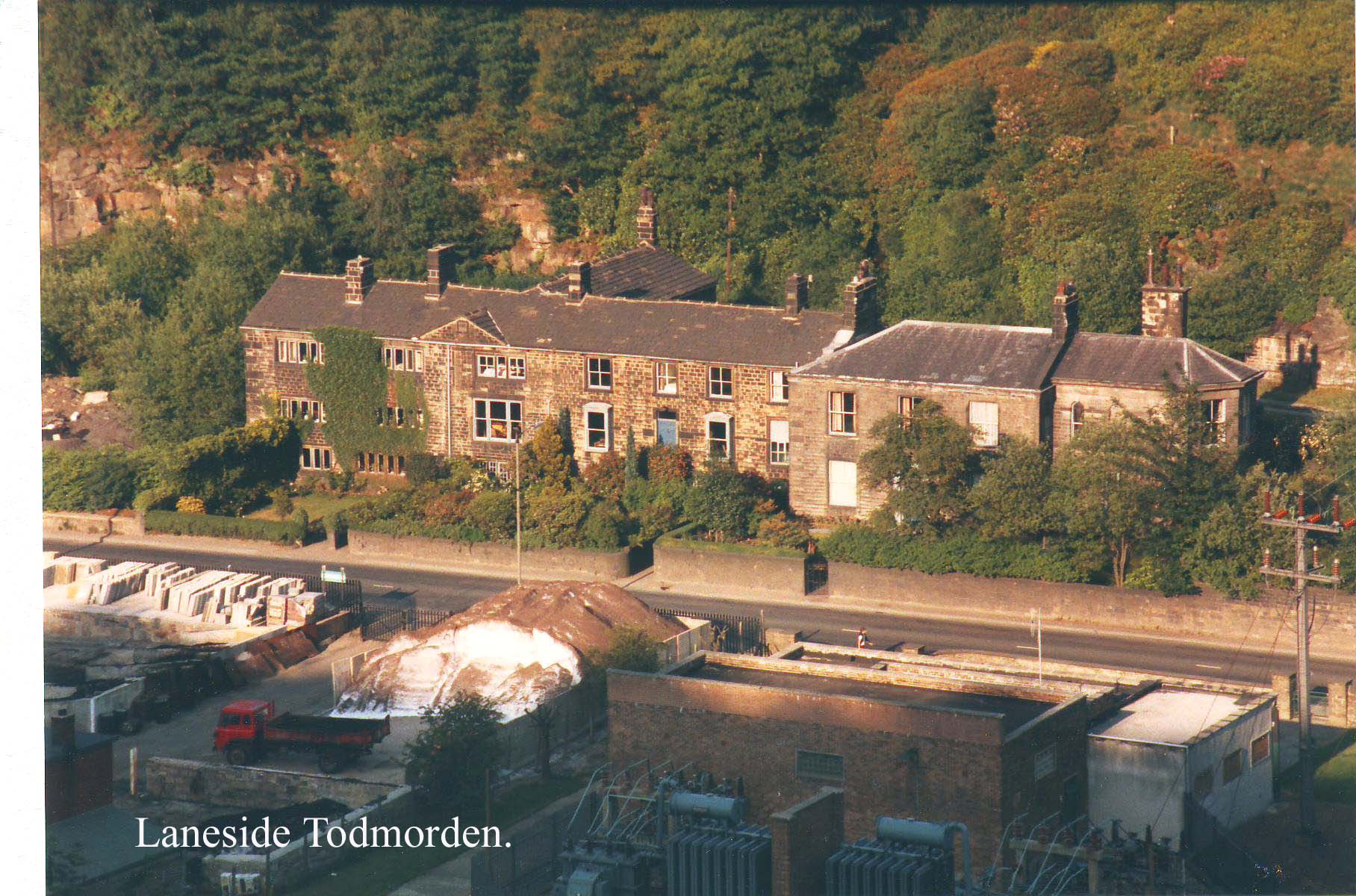

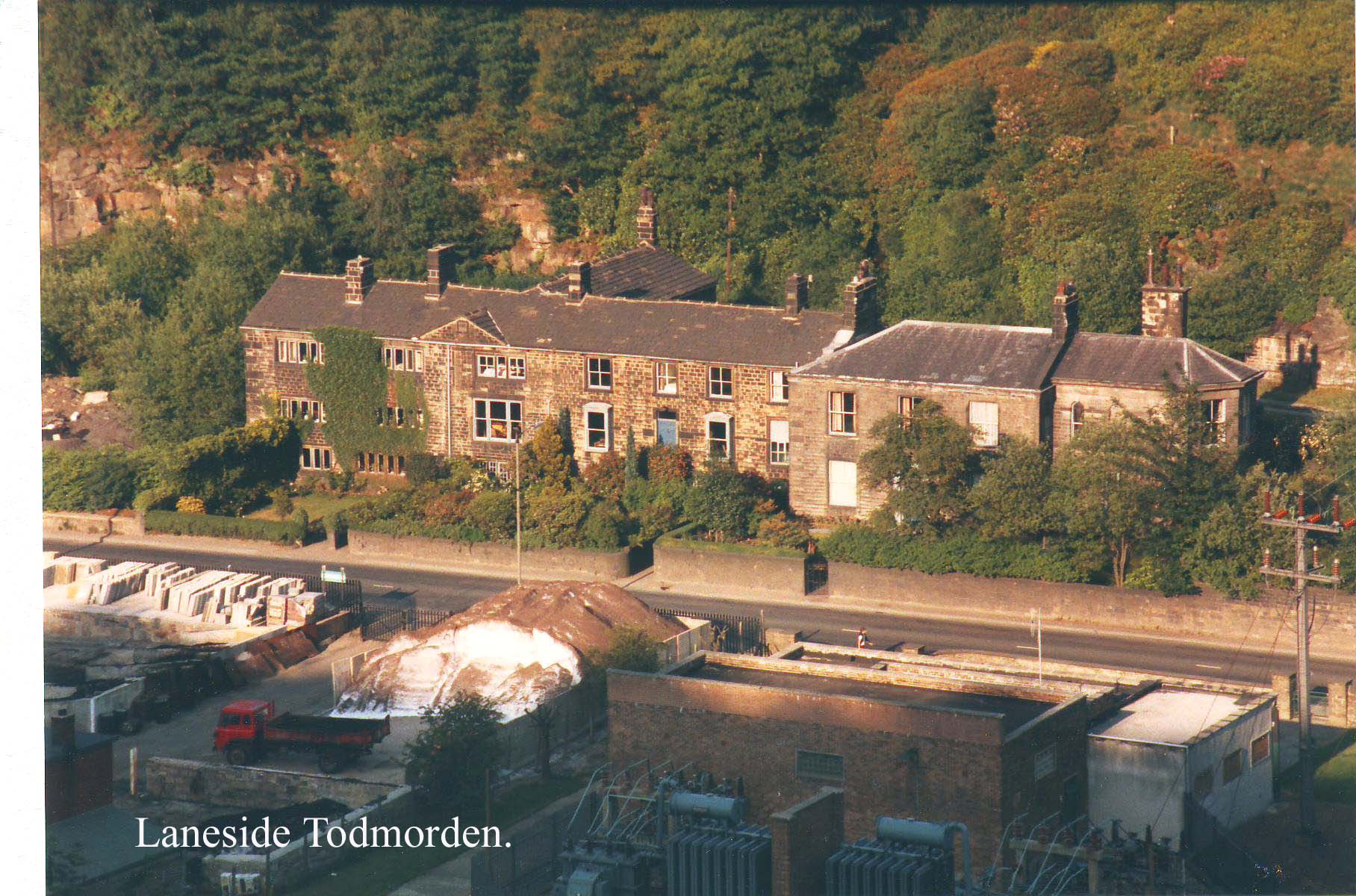

In 1782 Joshua Fielden (IV) sold Edge End, packed his bags, bought some spinning jennies and established his cotton business in cottages at Laneside. He could never have realised that in embarking upon this uncertain, risky venture he would be laying the foundations of an industrial empire destined to be one of the largest in the world, and

that his children would succeed to a wealth and fame far beyond his wildest imaginings.

From Edge End, continue onwards to the pretty gardens and interesting stone heads of Ping Hold which once had, as its name suggests, a pinfold, where stray animals were kept until they could be claimed from a pinderman on payment of a fine. From here the lane continues onwards, passing the strange, crenellated turrets of the 'model farm' on the Dobroyd Castle Estate, and eventually reaches a large house surrounded by trees, iron railings and a boulder outcrop almost leaning against the windows, which is called (appropriately enough) Stones.

At Stones once lived another Quaker family, the Greenwoods, who were substantial landowners hereabouts. The Stones' Greenwoods originated from Middle Langfield Farm, which was the home of John Greenwood from 1675. In such a closely knit community as this it was inevitable that sooner or later they would find themselves in dynastic alliance with their neighbours, the Fieldens, and so it was that on 4th June 1771 Jenny Greenwood, daughter of James and Sarah Greenwood of Langfield, married Joshua Fielden (IV) of Edge End at the local Friends' Meeting House. The union was fruitful, as she had five sons and four daughters (one of which died in infancy). The third son of her brood was to find lasting fame. He would grow up to become known as 'Honest John' Fielden, humanitarian, Member of Parliament and factory reformer.

Edge End Farm, home of Joshua Fielden.

Beyond Stones, follow a gradually descending gravelly lane, lined with occasional groups of trees. On the right is a TV mast, and on the left, when the track bears slightly to the right, we are treated to an extremely good view of...

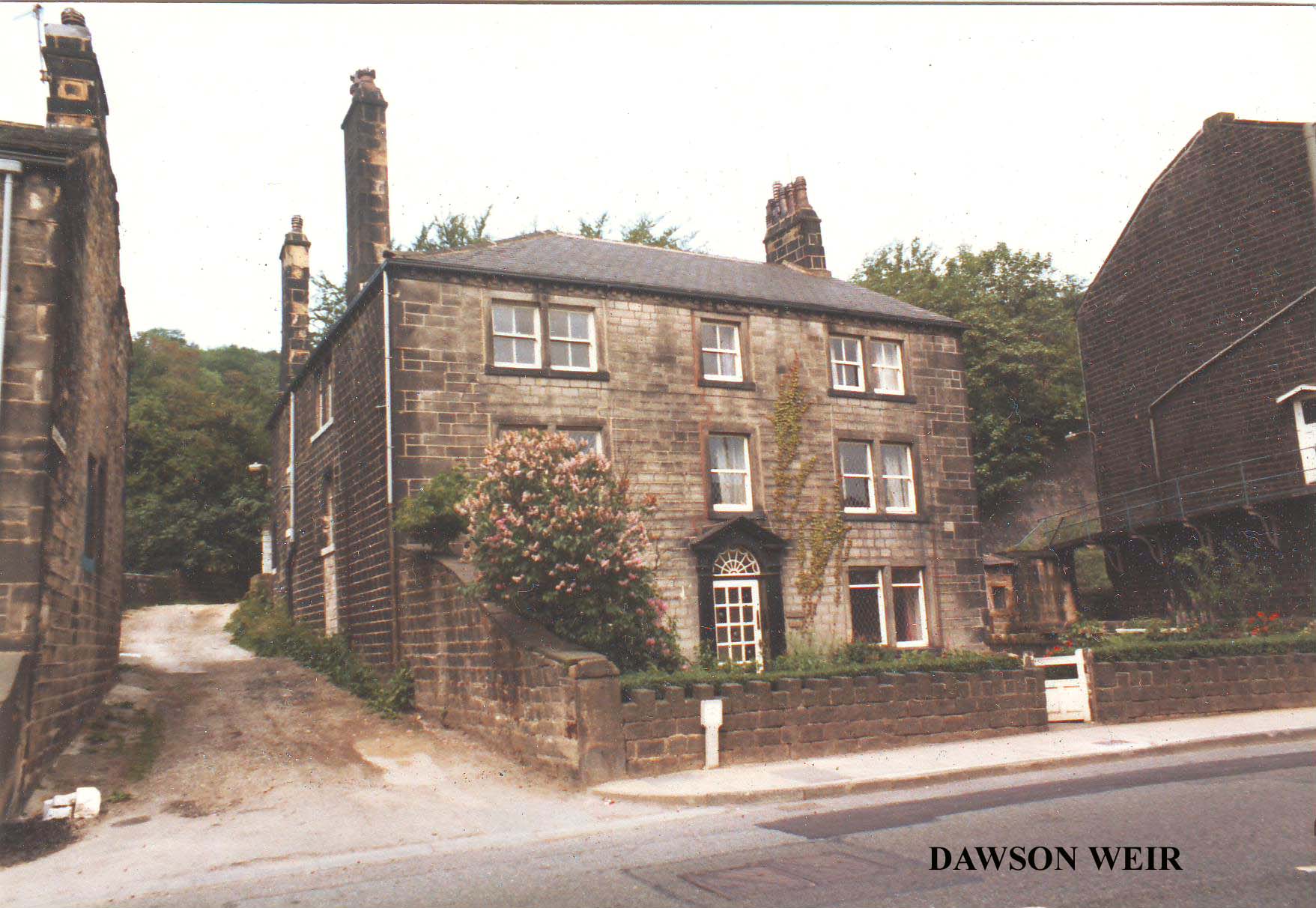

Dobroyd Castle

Dobroyd Castle is the second of the 'great houses' which were the residences of 'Honest John' Fielden's three sons. Stansfield Hall was, as we have seen, the residence of the youngest son, Joshua Fielden of Stansfield Hall and Nutfield Priory, Surrey. Dobroyd Castle, most certainly the grandest of the three houses, was the residence of the middle son, John Fielden J.P. of Dobroyd Castle and Grimston Park, Leeds.

Dobroyd Castle was built between 1865 and 1869 at a cost of 100,000 pounds When it was completed, 300 of the workmen involved in its construction were treated to a celebration dinner at the Lake Hotel, Hollingworth Lake. Like most of the Fieldens' later buildings, it was designed by John Gibson, who also designed Stansfield Hall.

John Fielden J.P. of Dobroyd Castle was a landowner in the grand style. He was appointed High Sheriff and J.P. in 1844. (However his father had refused to take a justices' oath in protest at the new Poor Law). By 1873 he owned 405 Lancashire acres and 2848 acres in Yorkshire. Ten years later his total rental was 9000 pounds. His grandfather Joshua (IV), the 'embryonic industrialist', had taken the Fieldens into the town. Grandson John returned them to the soil once more, but as landed gentry. John Fielden J.P. was the last surviving of 'Honest John's' three sons, dying in July 1893 at the age of 71. He had spent much of his life in a wheelchair as a result of a riding accident which shattered his leg. He was twice married, and in this context is the subject of an interesting story we will encounter further along the Fielden Trail.

Dobroyd Castle was purchased by the Home Office in the 1940's and became an approved school. It has since been a community home and a Buddhist Temple and is currently the Robinwood Outdoor Adventure Centre (2009).

After surveying Dobroyd Castle, continue onwards, following the Calderdale Way down Stones Road, passing a barn and cottage on the left. This is Pex House. Originally called Pighill, it was a substantial farm at one time. It ceased to be when it was sold to John Fielden in 1865, who at that time needed land on which to build his castle. The house was then occupied by Peter Ormerod, father of William Ormerod, the second mayor of Todmorden.

Beyond the barn the descent becomes steeper, and the road soon emerges onto a hairpin bend, perched precipitously on the edge of the

Dobroyd Castle. Residence of John Fielden J.P. of Grimston Park

valley overlooking Gauxholme. Below, looking almost like a scale model, the canal passes beneath the great skew bridge which carries the railway onto the Gauxholme Viaduct. Here is civilisation at last, mills, terraced houses and the sinews of industry.

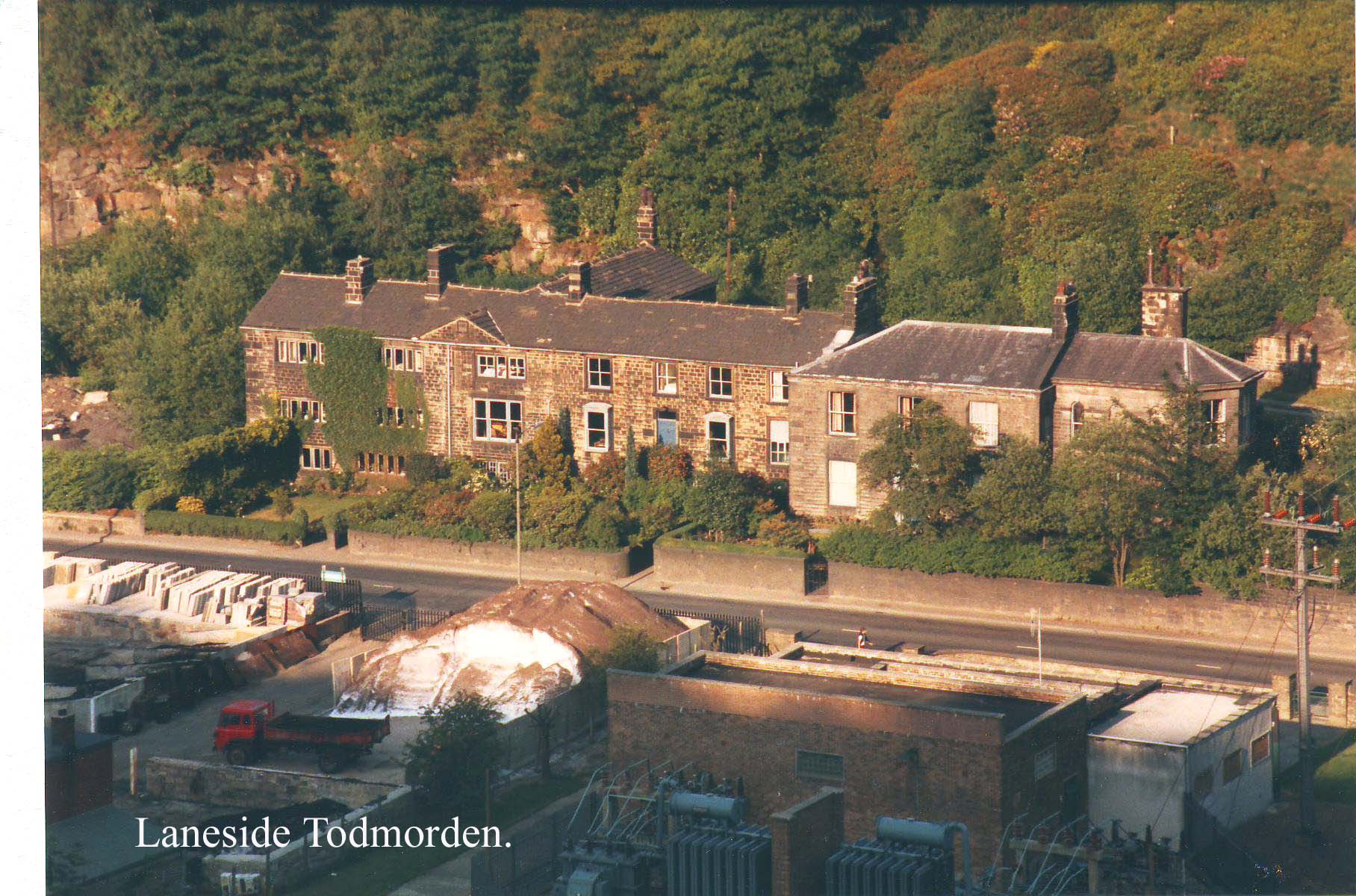

At the lodge gate leading to Dobroyd Castle, the metalled road bears sharp right and descends to the Bacup Road at Gauxholme where it meets up with Section 3 of the Fielden Trail (Pexwood Road). Our route however, continues onwards, (sign 'No Through Road'), descending through woodland towards Todmorden as it meanders above the railway. Below, alongside the main road, can be seen the cottages at Laneside in which Joshua (IV) set up his cotton business. Even the railway below us was utilised by the Fieldens' ever expanding industrial empire (they were after all directors of the railway company) ... sidings from the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway were run directly into the two warehouses at Dobroyd, and an overhead gantry carried consignments to and from the mills.

The lane descends to a kissing gate beside the railway line. From here a pedestrian level crossing leads over the tracks. You will notice that the lines are very shiny, that means they are used quite frequently, so please beware of trains!

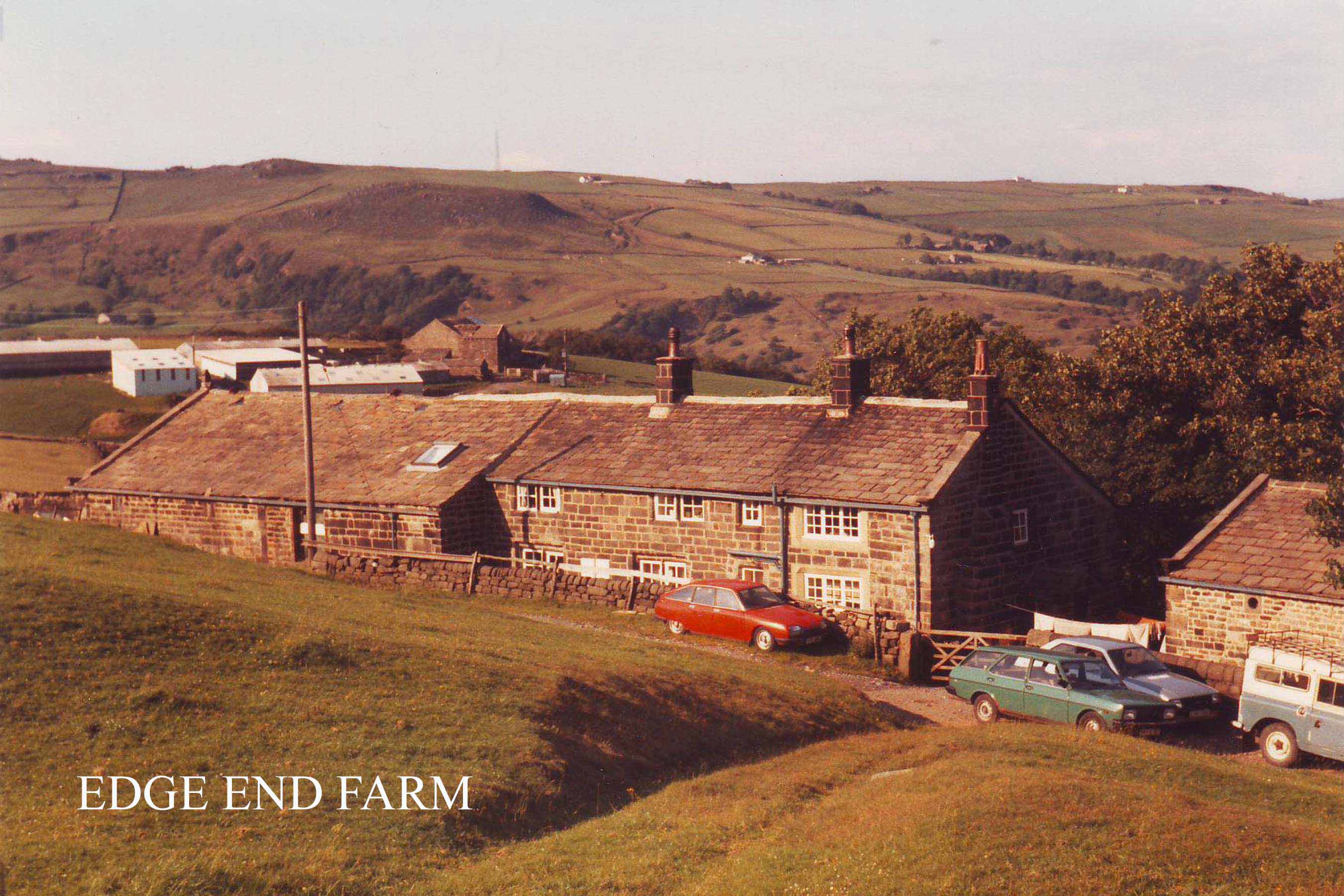

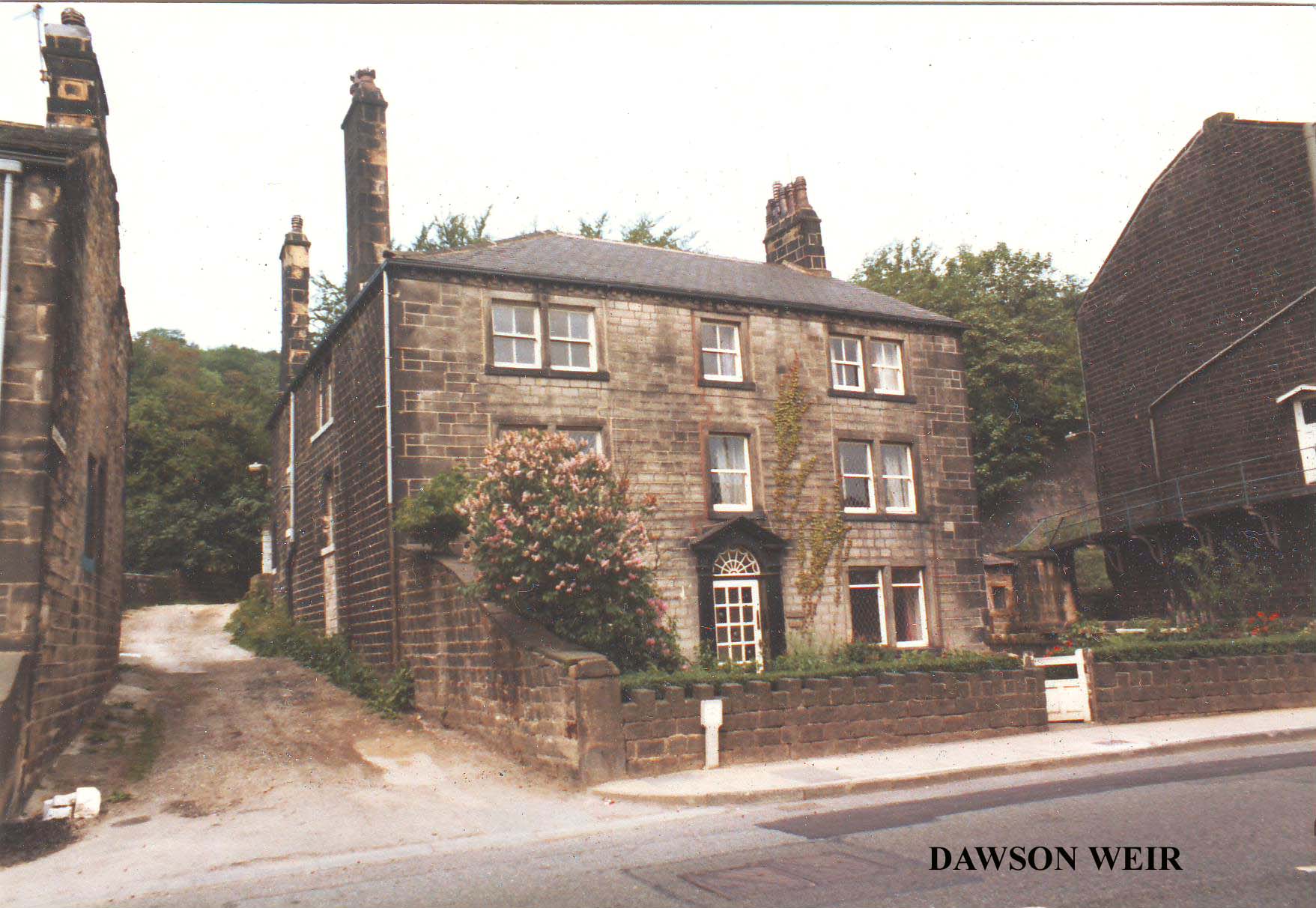

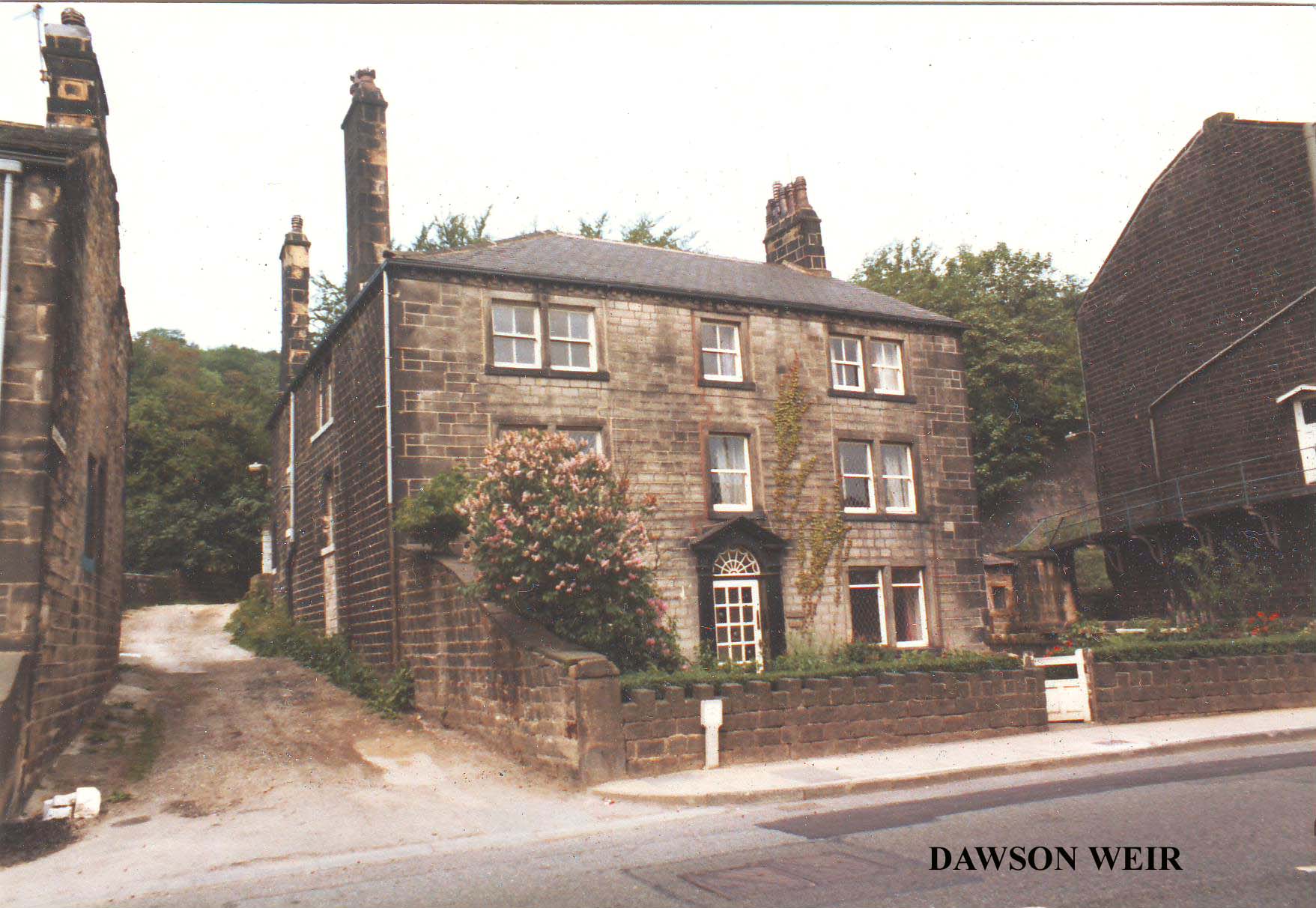

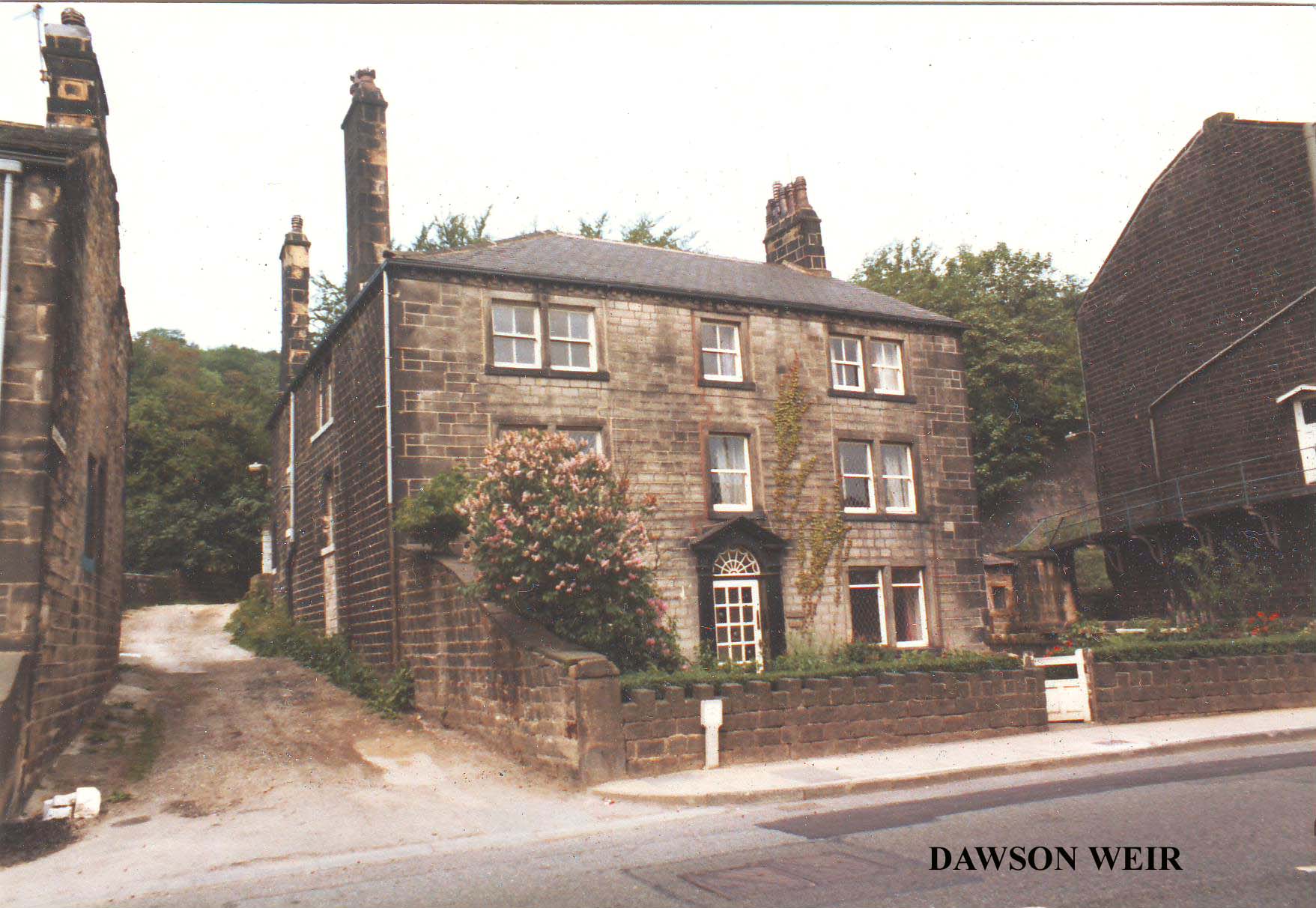

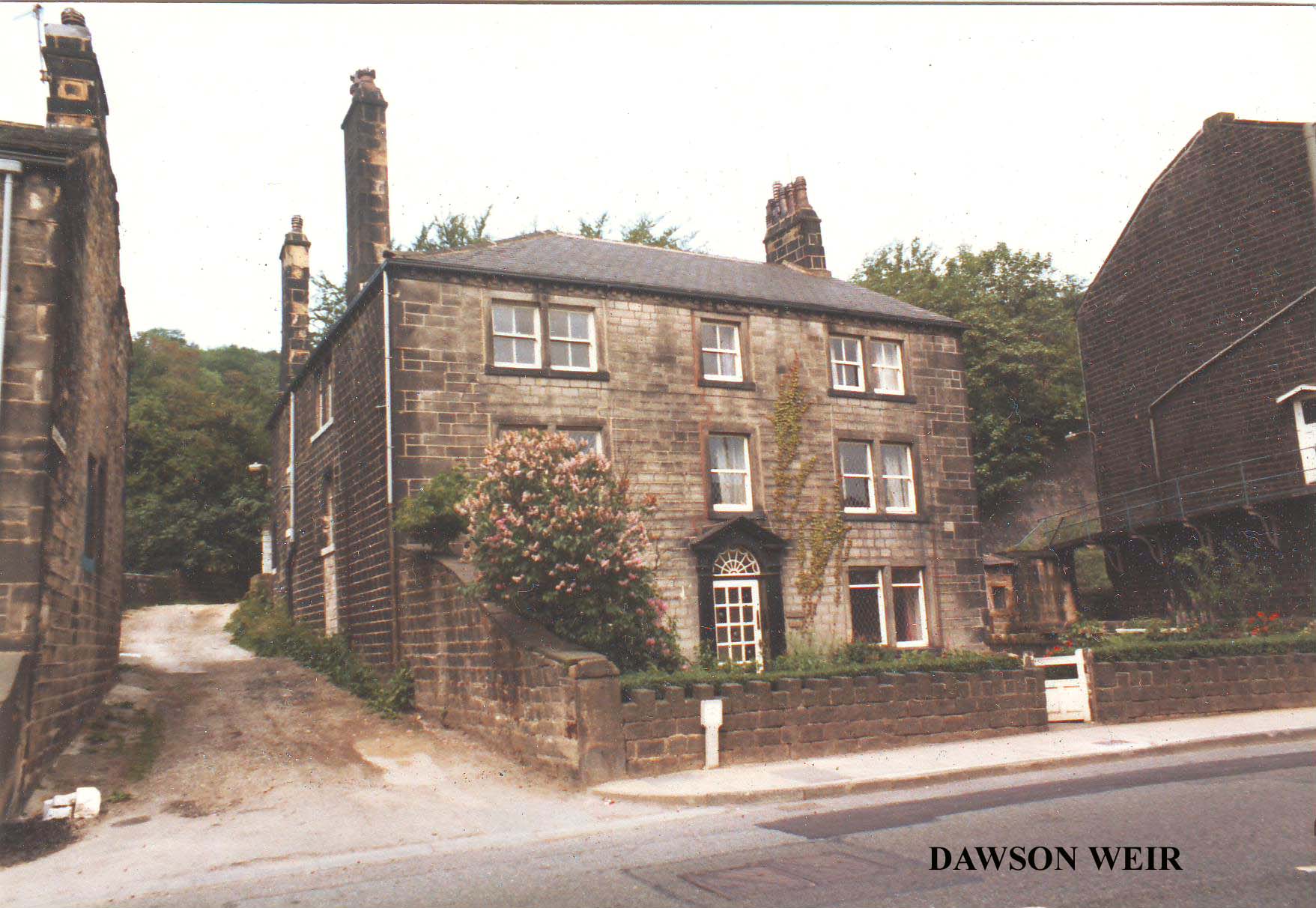

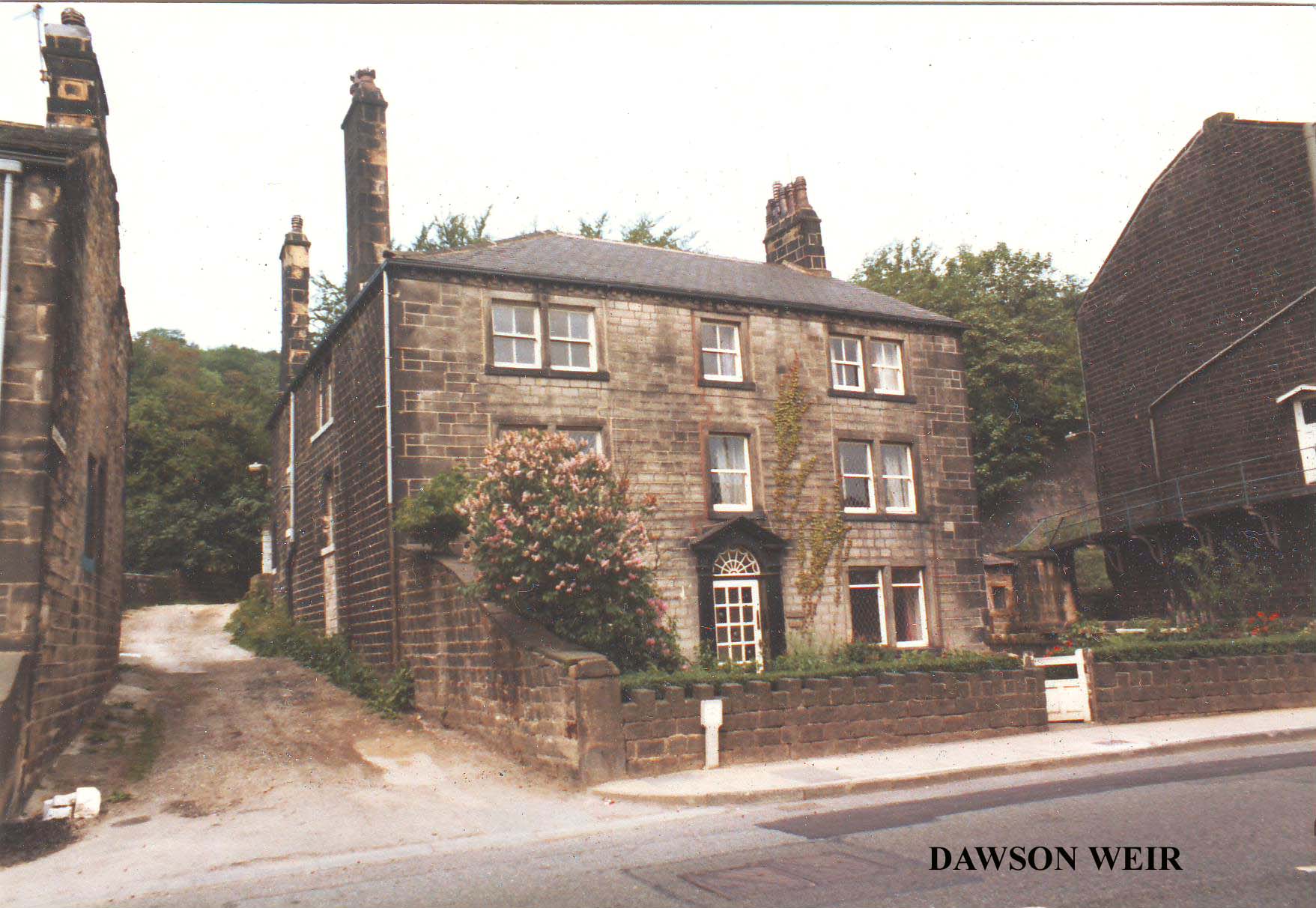

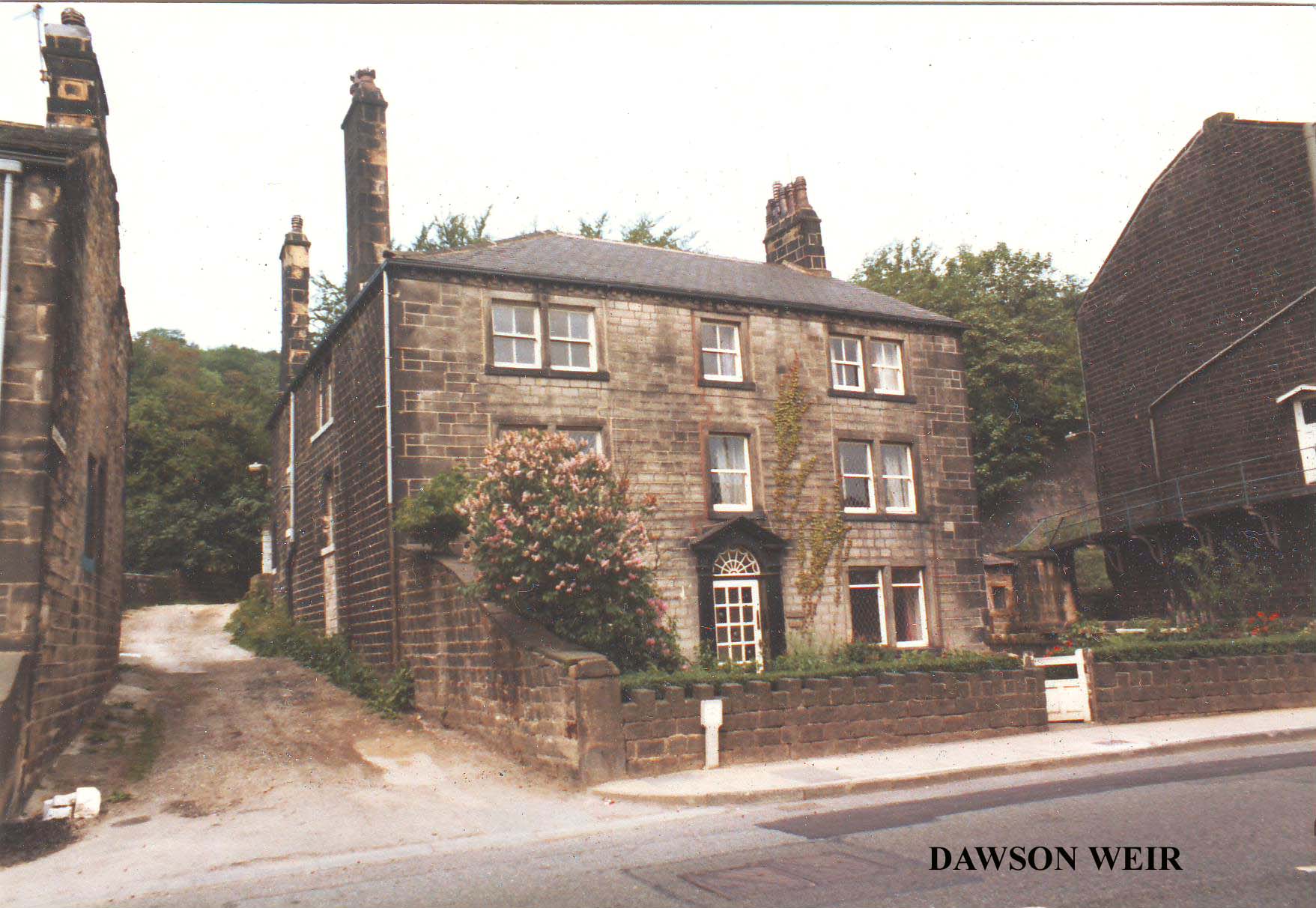

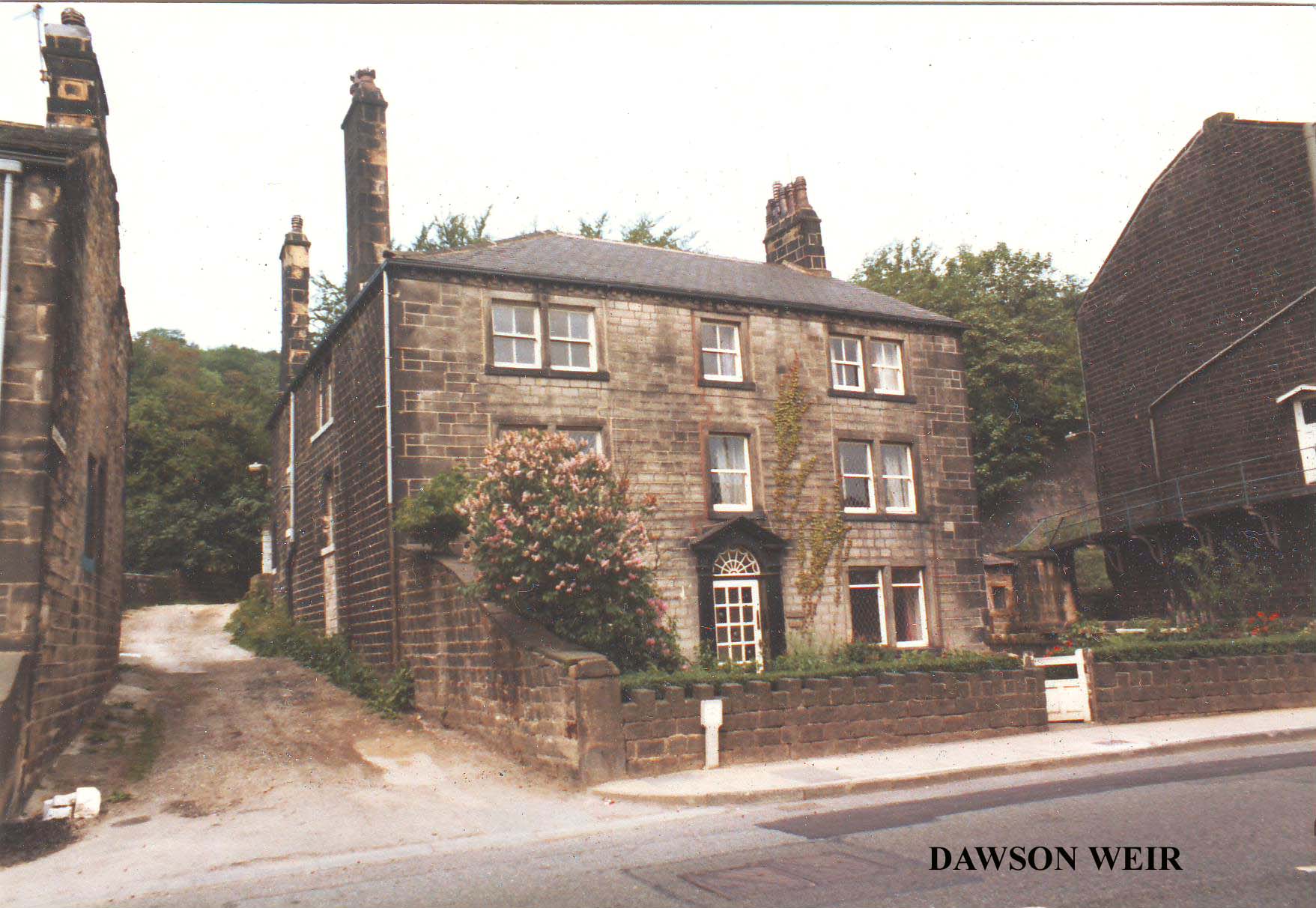

Having crossed the railway, bear left down to Dobroyd Road. Soon, an old stable block appears on the right, and just beyond it the route passes over the canal to emerge on the busy A6033 Todmorden to Rochdale Road at the side of Dawson Weir, which is the substantial georgian house on the left.

Dawson Weir

At Dawson Weir we stop and reflect awhile, for we have reached yet another chapter in the Fielden story. If you are in need of refreshment to assist this reflection and the hour be right, turn left along the road and treat yourself to fish and chips and pop at the nearby Waterside Chippy, truly scrumptious! Now retrace your steps to Dawson Weir.

On 12th September 1811 'Honest John' Fielden, third son of Joshua (IV) of Edge End and Laneside married Ann Grindrod of Rochdale at Rochdale Parish Church. He was 27 years old, newly married and seeking a home in which to settle down and start a family. The newlyweds set up house here in this fine three storeyed Georgian house sandwiched neatly between the turnpike and the canal. This was an age when manufacturers still lived close to their workers, and John

made a shrewd choice in settling here, right at the heart of the Fielden's expanding industrial empire.

I imagine Dawson Weir as being a happy household, echoing to the patter of children's feet and the murmer of kindly servants. John and Ann were certainly prolific, for in this house were born seven children... three sons and four daughters. The three sons were Samuel (b. 1816), John (b. 1822) and Joshua (b. 1827). The daughters were Jane (b. 1814), Mary (b.1817), Ann (b.1819) and Ellen (b. 1829). The three boys of course were the 'three brothers', two of which we have already encountered at Stansfield Hall and Dobroyd Castle. Their father was the son of a successful manufacturer who would soon go on to acquire a uniquely individual fame as M.P. for Oldham and a radical reformer; but in these days, although vastly wealthier than many of their neighbours, the Fieldens were nowhere near attaining those trappings of the landed gentry which 'Honest John's' three boys would come to enjoy in later life.

Life at Dawson Weir must have been genteel and moderately comfortable; wealthy by the standards of old Joshua's generation, but

Dawson Weir

quite bourgeois when set against the princely lifestyles of later Fieldens at Dobroyd Castle, Stansfield Hall and Centre Vale. The house looks rather like a parsonage, early 19th century middle class. A clergyman like Patrick Bronte would certainly have not found Dawson Weir above his station, and indeed the lifestyle of 'Honest John's' family at Dawson Weir must have been very like that which is now observable down to the smallest domestic details in the Bronte Parsonage Museum in Haworth.

But for some personal insights into domestic life there from the pen of John Fielden's second daughter, Mary, there would be little else to say in connection with Dawson Weir. There is nothing sensational in the letters, as they are, for the most part, the letters of a young and rather bossy nineteen year old 'big sister' to her 'kid brother' John at the St. Domingo House School in Liverpool. The letters do however, give insights into daily events in 19th century Todmorden. Here are some examples:

"Dawson Weir

May 10th 1836.

My Dear John

You are a very naughty boy not to have written to me since you returned to school ... I hope after you receive this that you will write and tell me you are alive. I expect my father will be coming here in a little more than a week as the Members of the House (of Commons) have a holiday of about ten days for Whitsuntide. All here are pretty well, you can tell John that Sam has exchanged the old cow for that horse that Sam has heard speak of and John Collinge has been breaking it in, and tell John that John Collinge says he thinks it will soon be ready for ME to ride. It will just do for a ladies' pony. Ask John if he does not think it will look a great deal better with me upon its back than with him.

The weather is so fine at present, it is a delightful change from the bad weather we have had. Sam is so industrious you cannot think, he often gets up at five o' clock in a morning and goes into the mill ...

Your affectionate sister,

Mary Fielden . . ."

It is not so hard to imagine Mary with her new pony. No doubt her brother's friend had designs on it also, as she seems to be rubbing it in that she had 'bested' him in getting the pony! No doubt she kept it in the old stable block we passed on the other side of the canal.

Not all of Mary's letters brought news so cheerful. Disease and death were constant companions in an age where sickness was rampant, and medical knowledge and hygiene virtually nonexistent. In the 1830s the average life expectancy was far lower than it is today. Infant mortality in particular was high, a fact which no doubt explains the tendency of early Victorians to beget large families. The Fielden children at Dawson Weir were luckier than many of their class, for all seven of them managed to grow up and take their place as adults; though their mother, Ann, died in 1831 when Mary was 14 (her youngest sister Ellen was only 2). No doubt she was, like many nineteenth century women, worn out with bearing children.

In 1834 John Fielden took a second wife, Elizabeth Dearden of the 'Haugh' in Halifax. Whether or not Mary liked her new stepmother is unknown, yet by 1836 she was attending yet another funeral, within months of getting her pony...

"Dawson Weir

September 18th 1836.

My Dear John

You will be very surprised and very sorry to hear that we have had another of our friends taken from us.... about half past twelve this morning my Aunt Lacy of Stoodley departed this life after an illness of more than a week . . . she had a paralytic stroke which deprived her of the use of her right side ... We saw my aunt yesterday, she appeared very ill and much altered in appearance since we had seen her the week before. My uncle Lacy is of course very much distressed, but wears the affliction as well as can be expected. Someone will write to you again, either tomorrow or Tuesday and inform you about your mourning."

Betty Lacy (nee Fielden), wife of Henry Lacy of Stoodley Hall, died at Stoodley Hall aged 60. She is buried in the Old Churchyard at Todmorden. The grim theme of sickness and death continues in other letters. Earlier in the same year Mary expressed concern over the condition of her mother, (actually her stepmother, Elizabeth Dearden), who had dropsy in the chest and was seriously ill. (Nowadays this would be diagnosed as severe bronchitis or pneumonia). The prescribed treatment for such a condition seems, to modern eyes, more severe than the condition itself:

"Doctor Henny told her that she required the greatest care, attention and quiet, that she has not to walk much, not to go down stairs and not to go uphill. He ordered her a blister and some medicine. She has a blister put on every other morning and lets it remain on for 24 hours when she has it taken off and some healing ointment put on . . . She is at the Haugh and will remain there, I suppose, until she is better. She went last Friday ... I do not wish you to tell anyone what my mother's complaint is as she might not much like it, and it may be better not .. .

Your attached sister,

Mary Fielden."

A 'blister' or 'blister plaster' was used medically in those days to raise blisters as a counter irritant, it was composed of a compound of Spanish Fly (cantharis), beeswax, resin and lard, to make an externally applied medication. Because of (or more likely despite!) this treatment, Mary's stepmother recovered, to die two years after her husband, in October 1851, at the age of 63.

By this time Mary Fielden had married in the January of the same year, at the age of 34. Her husband was John Morgan Cobbett, son of William Cobbett, the famous radical journalist and author, who was her father's close friend and fellow M.P. John Morgan Cobbett had attended her father's funeral in June 1849, and had no doubt consoled the grieving daughter. Certainly the Fieldens were no strangers to the Cobbetts, for in one of her letters in 1840 Mary states that "Mr. James and Mr. Richard Cobbett came here on Saturday night... Mr. Richard went back to Manchester this morning, but Mr. James is still here. . . " These were presumably John Morgan Cobbett's brothers. Perhaps Mary's husband to be was the 'John' who was at school with her brother, the one she 'bested' over the pony. Who knows? Whatever the case may have been, they were certainly well acquainted.

After her wedding Mary left Todmorden and went to live with her husband at Farnham, Surrey (where there is now a Cobbett Museum). She bore him two sons, John Fielden Cobbett and William Cobbett and a daughter, Mary. Her husband died in 1877 and is buried at Farnham.

We will leave Mary Fielden with an amusing but also sadly revealing anecdote. As Ian Dewhirst has pointed out in his History of Keighley, emigration caused by hardship, poverty and the threat of the workhouse was a common phenomenon in the 1840s and '50s. Even the penniless could escape abroad for a consideration; it was so easy, in fact, that men would often ship out for California or the Cape of Good Hope, abandoning wife and children to the workhouse:

"Dawson Weir.

March 23rd 1840.

to John Fielden M.P.

17 Panton Square

Westminster.

My Dear Father, have you heard that William Greenwood the grocer (who came to chapel) went along with Thomas Dawson to America. It is said that he is gone out of the way of his creditors because he is in debt, but I have heard that they can pay their debts, if they receive what is owing to them. He has left his wife and family behind, and is gone intending to buy a piece of land, and if he thinks he can do well he will either send for or fetch his family . . ."

We can only speculate as to whether or not he ever did. Perhaps there is someone now living in some part of the United States who can supply the answer?

We have now reached the end of Section 2. If you parked your car at the start of Section 1, you will find it just five minutes walk away. Simply turn left for Todmorden Town Centre. If, however, your car is at the beginning of Section 2, you will have to follow the Burnley Road all the way up to Cornholme (catch the Burnley bus.)

Copyright Jim Jarratt.

2006 First Published by Smith Settle 1989

Beyond Roundfield, the route continues and after avoiding a bad area of bog, arrives at another ruined farmhouse. Here a distinct track becomes a gravelly farm road, leading to Wet Shaw, which has just been rebuilt and hugs the hillside in the company of vans and rickety sheds. Continue onwards, following the farm road to New Towneley.

At New Towneley a choice must be made. If you continue onwards, following the track, you will arrive at West End, just beyond which you will be able to follow a descending track which will rejoin the main route above Flail Croft on its way to Todmorden Edge. This short cut will take time and effort off the journey, but will deny you the opportunity of seeing a spectacular bird's eye view of the Upper Calder Gorge and the imposing edifice of Robin Wood Mill, one of the Fieldens' many spinning mills. The Fielden Trail takes the latter option and heads towards the valley. Take the easy option if you like, but I'm going to Robin Wood Mill.

From New Towneley, follow an indistinct route down the pasture towards trees. Orchan Rocks can be seen directly opposite, on the other side of the valley. Halfway down the field the path is soon discovered on the left, running between a fence and a wall. Only trouble is, there's no way of getting to it, when you arrive at the field corner you can see the path leading out onto the crags, but you will have to climb over the fence to get to it. Once over the fence, turn right along the edge. just before the fence meets a wall, coming in from the right, a path may be seen descending the steep slope to the left, marked by a row of stakes. Follow this route down the hillside, and soon another path is met with, ascending from below left. This path comes up from Robin Wood Mill at Lydgate, which can be seen in the valley below.

Robin Wood Mill

This tall, grey edifice, nestling at the bottom of the valley, was once one of the Fieldens' spinning mills. Severely classical in design, it still manages to look imposing, despite broken windows and the fact that much of it now appears to be derelict.(AUTHORS NOTE. There was a fire not long after the Fielden Trail was published and now the mill is sadly reduced, much of it having been demolished!) What premises are still in use are the premises of The Todmorden Glass Co.

What a handsome building it is.(was!) A cotton mill, yes, but quite unlike the Mons Mill further down the valley, which is more typical of a later generation of Lancashire cotton mills, those red brick giants which dominate the landscape around Rochdale, Bury, Oldham and Manchester. Nearby is Fielden View and Robinwood Terrace, a uniform group of houses built in 1864 to house some of the Fieldens' workers perhaps? Even now, in decay, the community is dominated by the mill and the adjacent railway viaduct.

At this point perhaps we ought to take a look at the cotton industry, which made the Fieldens their fortunes and is therefore closely bound up with the subject of this book. The cotton industry was literally created by self made men like the Fieldens between the years 1770 and 1840 in a period of spectacular growth. It continued to expand, reaching its peak in 1912 when 8 million yards of cotton were produced. After this date increasing foreign competition along with various other factors were to bring about the gradual decline of the industry. By 1803 cotton had already overtaken wool as Britain's leading export, quite an achievement for an industry based entirely on imported raw materials. The reasons for this sudden boom are varied. The invention of the Saw Gin by Eli Whitney was certainly a contributory factor to cotton's phenomenal growth, for it opened up a supply of cotton from the Southern United States at a time when other sources, for example the West Indies, were beginning to prove inadequate. U.S. growers consistently reduced their prices up to 1898, and this enabled Lancashire to create an industry which was to make the whole world its market.

Why Lancashire? Basically because it had all the right qualifications: cheap land, coal, and soft water which was ideal for bleaching, dyeing and printing, not to mention the powering of machinery. In Liverpool, facing the Americas, 'King Cotton' was to find his port, and in Manchester his market. In Lancashire there were fewer restrictive practices like guilds and ancient corporations to hinder the development of the new industry. In many ways preindustrial Lancashire was rough, wild and poorly developed, but for the building of a cotton industry conditions were ideal, and, when it came, the growth was simply phenomenal.

The technology which made such a growth possible had been developing for some time. In 1733 the 'Flying Shuttle' devised by John Kay of Bury triggered off a whole pattern of invention which was to transform the whole social and economic structure of those northern regions involved in textile industries. In 1760 came Hargreaves' 'Spinning Jenny', and in the 1770's Arkwright's 'Water Frame'. 1779 saw the invention of Crompton's 'Spinning Mule' and 1785 Cartwright's Power Loom. The development of the steam engine by James Watt ensured the gradual changeover from waterwheels and goits (artificial watercourses) to boilers and mill engines, with subsequent changes in the priorities of mill siting. The demand for coal rather than water and the need for inlets and outlets of raw and finished materials were to bring improved communications in the form of canals, and later, railways. The spate of inventions continued throghout the 19th century: Radcliffe's Dressing Machine (1803) prepared threads for weaving; Dickinson's 'Blackburn Loom' (1828) introduced picking staves; The 'Self Regulating Mule'; 'Ring Spinning'; 'Northrop Looms'; the list goes on, and on, and on.

The production of cotton cloth did not only involve spinning and weaving. The cloth had to be 'finished' and dyed, and a whole series of inventions and processes evolved to improve this area of the industry. Early methods of finishing were costly and slow. This was particularly true of 'bleaching', which in the late 18th century required many acres of grassland for exposing cloth to sunlight and water (crofting). Another process, 'bowking', immersed the cloth in alkaline lyes concocted from the ashes of trees and various plants. Cloth was 'soured' in buttermilk and washed in 'becks' filled with running water, all complex and time consuming processes.

Then came the changes. In 1750 the use of dilute sulphuric acid reduced the time taken for souring by half. In 1785 the French chemist Berthollet devised a chloride of lime bleaching powder. New methods of mass producing bleacher's materials like soda ash,' caustic

soda and chlorine gas were also introduced in the 19th century. 1828 saw the introduction

of Bentley's 'Washing Machine'; and in 1845 Brook's Sunnyside Print Works in

Crawshawbooth used steam power to carry the ropes of cloth through all the stages of the bleaching process. 1860 saw the use of caustic soda by John Mercer of Clayton le Moors to produce a silken finish on the cloth, known as 'Mercerisation', and in 1856 Perkins succeeded in extracting mauve aniline dye from coal tar, which up to that time had been a waste product from the gasworks. Previous methods of dyeing had involved up to 19 different processes, including immersion in cow muck!

The impact of all this development upon Lancashire was immense. The whole region was transformed where King Cotton held sway. Cotton brought new mills, machinery, houses, canals and railways. New communities came into being. The development of Todmorden

The Fieldens' spinning mill at Robin Wood, Lydgate.

from a small hamlet into a substantial mill town was almost entirely due to the cotton trade. The mill owner and his operatives were but the tip of the iceberg, a host of interests were involved, from engineers, architects and builders, to chemists, bankers and financiers. Cotton created a demand for textile machinery, steam engines and boilers, houses, gas, electricity and transport. As a result of the cotton boom, Britain's best engineering skills were concentrated in and around Lancashire; and Merseyside's chemical industry owes its origin to cotton's consumption of dyestuffs, bleaching powders and soap. Mining, ironfounding and glassmaking also served the cotton industry. Indeed, it seemed that King Cotton was everyone's employer.

Prosperity and growth however, were not the only new developments at the court of King Cotton. There were other, less agreeable 'innovations' like bad housing and sanitation, grinding poverty, child labour, dangerous working conditions, and, most significantly of all, unbearably long hours. "Overwork," wrote Leon Faucher in 1884, "is a disease which Lancashire has inflicted upon England, and which England in turn has inflicted upon Europe."

It was in this context that the name of Fielden was to become universally esteemed, and to earn a fame far more enduring than that of mere charitable mill magnates, as we shall see. The Fieldens saw the benefits that might be derived from the factory system, but, unlike most of their class, they were painfully aware of the evils it created, and took steps not only towards easing the lot of the working man, but also towards his political emancipation, as we shall soon discover.

The next section of the Fielden Trail leads to Todmorden Edge. After meeting the path coming up from Robin Wood Mill, continue onwards and slightly upwards, contouring round the hillside. Soon there are good views down the valley towards Todmorden, with Centre Vale Park and the Mons spinning mill in the foreground.(AUTHORS NOTE Since demolished!) Mons is a much later mill than Fielden's at Robin Wood, and was built on The Holme, a large open space where fairs and circuses were formerly held. Opposite the remains of Royd House, which is now just a pile of stones overgrown with elder trees, join an ascending track in a gully (passing yet another ruin) which soon arrives at a rusty old gate facing West End on the hillside, to the right of another farm, Dike Green. Here the alternative route from New Towneley is met with. If anybody decided to miss Robin Wood Mill from the itinerary and take the short cut, they will be waiting for you here. Now turn left (you will have to climb over the wooden gate) and follow a green track past the head of Scaitcliffe Clough. At Flail Croft nearby, lived (in 1714) Samuel Fielden, brother of Nicholas of Edge End, and John of Todmorden Hall, both of whom we will encounter later. Continue onwards until a wall and wooden gate are joined (on left). Pass through this gate, and be careful when you shut it, as when I did so I was miles away in thought and did not see the eye level barbed wire which made a neat little cut on my forehead! Beyond a stone in the wall on which is carved the letters I M bear left across the fields to enter the lane leading to Todmorden Edge.

Todmorden Edge

If Nonconformism had shrines then Todmorden Edge would certainly be one of them, for it has associations with both the early Quakers and the early Methodists. Quaker meetings were held at Todmorden Edge Farm and, as at Shore, there is a 'Quaker Pasture'. Early Quakers were persecuted, and Todmorden Edge has seen its share of that. Henry Crabtree, who was curate of Todmorden in the 1680s, viewed the Friends with great distaste. With Simeon Smith, his servant, he surprised a number of Quakers from Walsden and Todmorden when met together at the house of Daniel Sutcliffe, at Rodhill Hey on May 3rd 1684. A fine of five shillings was imposed on each person present. As the fines were not paid, distraints were made on their goods. A month later, a meeting in Henry Kailey's house at Todmorden Edge was similarly disturbed and goods to the value of 20 pounds, an ark of oatmeal, and a pack of wool were taken.

Todmorden must have been noted for the number of Friends, for when those who declined to pay for repairs to the church and school at Rochdale were summoned by the Rochdale Churchwardens, it was stated that the majority of the offenders came from Todmorden, where Quakers were "both numerous and troublesome". Fortunately for the Fieldens and others of their faith 1689 saw the passing of the Toleration Act, which enabled Quakers to register their meeting houses officially for the first time.

In the wake of the Quakers came the Methodists. On 1st May 1747, John Wesley preached

at Shore at midday; then later, at Todmorden Edge Farm, he called "a serious people to

repent and believe in the Gospel". The following year, on October 18th 1748, the

first recorded quarterly meeting ever held in Methodism took place at Chapel House,

Todmorden Edge, under the chairmanship of that noted religious firebrand William

Grimshaw (who was curate of Todmorden before his more famous association with

Haworth). Methodism obtained many converts, and the Friend's Meeting House at Todmorden Edge, along with a Meeting House and a Baptist Chapel at Rodhill End, were sold to the Wesleyans.

The Fieldens, unlike many of their Quaker brethren, were not converted to Methodism. They remained Quakers, but for all that the Methodists were to play an important part in the establishment of Unitarianism in Todmorden, with which the Fieldens were actively

involved.

From Todmorden Edge the Fielden Trail moves on to Edge End, the home of Todmorden's first industrial entrepreneur, and father of 'Honest John' Fielden, Joshua Fielden of Edge End. As we leave Todmorden Edge with its Wesleyan associations it is perhaps worth bearing in mind that John Wesley, for all his goodness and unwavering faith, went so far as to recommend child labour as a "means of preventing youthful vice". John Fielden, who was born 36 years later in 1784, would hardly have agreed with such a sentiment.

On meeting the Calderdale Way by the stables at Todmorden Edge Farm, bear right, following the concreted farm road past a white gate to where it meets tarmac at Parkin Lane. From here the route continues without difficulty (following the Calderdale Way) to......

Edge End Farm

At Edge End we come to an important chapter in the Fielden story. Here is the scene of the Fielden's transition from farming and wool to industry and cotton. This low, embattled stone farmhouse hugging the hillside was where the Industrial Revolution in Todmorden was born. The initiator of the chain of events which was so greatly to transform the fortunes of both the Fieldens and those around them was Joshua Fielden, 'Honest John's' father. Joshua Fielden was not the first of that name, nor would he be the last. His second son was called Joshua, and he was to have a grandson and a great grandson of the same name. As if that was not confusing enough, we also find that his father, grandfather and great grandfather were also called Joshua! Because of this I have found it necessary to number all these 'Joshuas' in the hope of lending at least a little clarity to a confusing and misleading situation.

Back at Hartley Royd we discussed Abraham Fielden of Inchfield who married Elizabeth

Fielden of Bottomley in the early 17th century. Their third son, Joshua Fielden of

Bottomley, although not the first Fielden to bear that name, was certainly the first Joshua in his

line, so for that reason I have referred to him as Joshua (I). From him the Joshua Fieldens of Bottomley and Edge End run as follows:

JOSHUA FIELDEN (I) of Bottomley Quaker. Received Bottomley from brother John of Hartley Royd. Died 1693.

JOSHUA FIELDEN (II) of Bottomley. Died 27th February 1715.

JOSHUA FIELDEN (III) of Edge End. Born Bottomley. Died at Dobroyd. (1701....1781)

JOSHUA FIELDEN (IV) of Edge End and later Waterside.

(1748...1811).

From this we can see that 'Honest John's' father was the fourth successive Joshua in his line. Joshua Fielden (IV) was a Quaker like his forebears, and who lived in "a bleak, pious fashion" at Edge End Farm. His uncle Abraham (1704...1779) had inherited property at Todmorden Hall (this is a connection we will explore later) and was actively involved in the domestic textile industry. Joshua too, like most of the farmers around him, was involved in the production of woollen cloth, which was the traditional occupation of the whole district. By the mid 18th century the domestic system of cloth production had reached the height of its importance. Originally the farmer weaver simply produced his cloth at home and carried it to market (a cloth hall had been established as early as 1550 by the Waterhouse family of Shibden). Soon however, the business diversified and expanded: weavers collected into small settlements, the weaving hamlets linked by causeys and packhorse ways; while local merchants often acted as middlemen, selling raw wool to the weavers and buying back the finished cloth. As a result of this, in the 17th and early 18th centuries prosperous clothiers' houses began to appear, many of them with a "takkin' in shop" alongside. By the mid 17th century Halifax had its own cloth hall, but did not completely supersede the Heptonstall one until the Halifax Piece Hall was opened in 1779.

Joshua Fielden, like most farmerweavers in the Upper Calder Valley, had to work hard for his living. He attended Friends' weekly meetings at Shoebroad, farmed, wove his cloth and every weekend walked to the Halifax market and back with the cloth 'pieces' on his shoulders, a distance of 24 miles. Yet times were changing in the latter years of the 18th century. Maybe Joshua was getting a bad back and sore feet, or perhaps he simply had an eye for the main chance. Whatever his reasons, Fielden realised (in the words of J. T. Ward) that "Todmorden's geography permitted its embryonic industrialists to choose between cotton and wool." It was time to make that choice and Joshua chose cotton, a new material that perhaps offered more exciting prospects than the stolid, traditional pursuits of his forefathers.

Whatever his reasons may have been, Joshua Fielden turned his back on Halifax and was drawn westwards to the markets of Bolton and Manchester. It was time to break away from the established way of things.

In 1782 Joshua Fielden (IV) sold Edge End, packed his bags, bought some spinning jennies and established his cotton business in cottages at Laneside. He could never have realised that in embarking upon this uncertain, risky venture he would be laying the foundations of an industrial empire destined to be one of the largest in the world, and

that his children would succeed to a wealth and fame far beyond his wildest imaginings.

From Edge End, continue onwards to the pretty gardens and interesting stone heads of Ping Hold which once had, as its name suggests, a pinfold, where stray animals were kept until they could be claimed from a pinderman on payment of a fine. From here the lane continues onwards, passing the strange, crenellated turrets of the 'model farm' on the Dobroyd Castle Estate, and eventually reaches a large house surrounded by trees, iron railings and a boulder outcrop almost leaning against the windows, which is called (appropriately enough) Stones.

At Stones once lived another Quaker family, the Greenwoods, who were substantial landowners hereabouts. The Stones' Greenwoods originated from Middle Langfield Farm, which was the home of John Greenwood from 1675. In such a closely knit community as this it was inevitable that sooner or later they would find themselves in dynastic alliance with their neighbours, the Fieldens, and so it was that on 4th June 1771 Jenny Greenwood, daughter of James and Sarah Greenwood of Langfield, married Joshua Fielden (IV) of Edge End at the local Friends' Meeting House. The union was fruitful, as she had five sons and four daughters (one of which died in infancy). The third son of her brood was to find lasting fame. He would grow up to become known as 'Honest John' Fielden, humanitarian, Member of Parliament and factory reformer.

Edge End Farm, home of Joshua Fielden.

Beyond Stones, follow a gradually descending gravelly lane, lined with occasional groups of trees. On the right is a TV mast, and on the left, when the track bears slightly to the right, we are treated to an extremely good view of...

Dobroyd Castle

Dobroyd Castle is the second of the 'great houses' which were the residences of 'Honest John' Fielden's three sons. Stansfield Hall was, as we have seen, the residence of the youngest son, Joshua Fielden of Stansfield Hall and Nutfield Priory, Surrey. Dobroyd Castle, most certainly the grandest of the three houses, was the residence of the middle son, John Fielden J.P. of Dobroyd Castle and Grimston Park, Leeds.

Dobroyd Castle was built between 1865 and 1869 at a cost of 100,000 pounds When it was completed, 300 of the workmen involved in its construction were treated to a celebration dinner at the Lake Hotel, Hollingworth Lake. Like most of the Fieldens' later buildings, it was designed by John Gibson, who also designed Stansfield Hall.

John Fielden J.P. of Dobroyd Castle was a landowner in the grand style. He was appointed High Sheriff and J.P. in 1844. (However his father had refused to take a justices' oath in protest at the new Poor Law). By 1873 he owned 405 Lancashire acres and 2848 acres in Yorkshire. Ten years later his total rental was 9000 pounds. His grandfather Joshua (IV), the 'embryonic industrialist', had taken the Fieldens into the town. Grandson John returned them to the soil once more, but as landed gentry. John Fielden J.P. was the last surviving of 'Honest John's' three sons, dying in July 1893 at the age of 71. He had spent much of his life in a wheelchair as a result of a riding accident which shattered his leg. He was twice married, and in this context is the subject of an interesting story we will encounter further along the Fielden Trail.

Dobroyd Castle was purchased by the Home Office in the 1940's and became an approved school. It has since been a community home and a Buddhist Temple and is currently the Robinwood Outdoor Adventure Centre (2009).

After surveying Dobroyd Castle, continue onwards, following the Calderdale Way down Stones Road, passing a barn and cottage on the left. This is Pex House. Originally called Pighill, it was a substantial farm at one time. It ceased to be when it was sold to John Fielden in 1865, who at that time needed land on which to build his castle. The house was then occupied by Peter Ormerod, father of William Ormerod, the second mayor of Todmorden.

Beyond the barn the descent becomes steeper, and the road soon emerges onto a hairpin bend, perched precipitously on the edge of the

Dobroyd Castle. Residence of John Fielden J.P. of Grimston Park

valley overlooking Gauxholme. Below, looking almost like a scale model, the canal passes beneath the great skew bridge which carries the railway onto the Gauxholme Viaduct. Here is civilisation at last, mills, terraced houses and the sinews of industry.

At the lodge gate leading to Dobroyd Castle, the metalled road bears sharp right and descends to the Bacup Road at Gauxholme where it meets up with Section 3 of the Fielden Trail (Pexwood Road). Our route however, continues onwards, (sign 'No Through Road'), descending through woodland towards Todmorden as it meanders above the railway. Below, alongside the main road, can be seen the cottages at Laneside in which Joshua (IV) set up his cotton business. Even the railway below us was utilised by the Fieldens' ever expanding industrial empire (they were after all directors of the railway company) ... sidings from the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway were run directly into the two warehouses at Dobroyd, and an overhead gantry carried consignments to and from the mills.

The lane descends to a kissing gate beside the railway line. From here a pedestrian level crossing leads over the tracks. You will notice that the lines are very shiny, that means they are used quite frequently, so please beware of trains!

Having crossed the railway, bear left down to Dobroyd Road. Soon, an old stable block appears on the right, and just beyond it the route passes over the canal to emerge on the busy A6033 Todmorden to Rochdale Road at the side of Dawson Weir, which is the substantial georgian house on the left.

Dawson Weir

At Dawson Weir we stop and reflect awhile, for we have reached yet another chapter in the Fielden story. If you are in need of refreshment to assist this reflection and the hour be right, turn left along the road and treat yourself to fish and chips and pop at the nearby Waterside Chippy, truly scrumptious! Now retrace your steps to Dawson Weir.

On 12th September 1811 'Honest John' Fielden, third son of Joshua (IV) of Edge End and Laneside married Ann Grindrod of Rochdale at Rochdale Parish Church. He was 27 years old, newly married and seeking a home in which to settle down and start a family. The newlyweds set up house here in this fine three storeyed Georgian house sandwiched neatly between the turnpike and the canal. This was an age when manufacturers still lived close to their workers, and John

made a shrewd choice in settling here, right at the heart of the Fielden's expanding industrial empire.

I imagine Dawson Weir as being a happy household, echoing to the patter of children's feet and the murmer of kindly servants. John and Ann were certainly prolific, for in this house were born seven children... three sons and four daughters. The three sons were Samuel (b. 1816), John (b. 1822) and Joshua (b. 1827). The daughters were Jane (b. 1814), Mary (b.1817), Ann (b.1819) and Ellen (b. 1829). The three boys of course were the 'three brothers', two of which we have already encountered at Stansfield Hall and Dobroyd Castle. Their father was the son of a successful manufacturer who would soon go on to acquire a uniquely individual fame as M.P. for Oldham and a radical reformer; but in these days, although vastly wealthier than many of their neighbours, the Fieldens were nowhere near attaining those trappings of the landed gentry which 'Honest John's' three boys would come to enjoy in later life.

Life at Dawson Weir must have been genteel and moderately comfortable; wealthy by the standards of old Joshua's generation, but

Dawson Weir

quite bourgeois when set against the princely lifestyles of later Fieldens at Dobroyd Castle, Stansfield Hall and Centre Vale. The house looks rather like a parsonage, early 19th century middle class. A clergyman like Patrick Bronte would certainly have not found Dawson Weir above his station, and indeed the lifestyle of 'Honest John's' family at Dawson Weir must have been very like that which is now observable down to the smallest domestic details in the Bronte Parsonage Museum in Haworth.

But for some personal insights into domestic life there from the pen of John Fielden's second daughter, Mary, there would be little else to say in connection with Dawson Weir. There is nothing sensational in the letters, as they are, for the most part, the letters of a young and rather bossy nineteen year old 'big sister' to her 'kid brother' John at the St. Domingo House School in Liverpool. The letters do however, give insights into daily events in 19th century Todmorden. Here are some examples:

"Dawson Weir

May 10th 1836.

My Dear John

You are a very naughty boy not to have written to me since you returned to school ... I hope after you receive this that you will write and tell me you are alive. I expect my father will be coming here in a little more than a week as the Members of the House (of Commons) have a holiday of about ten days for Whitsuntide. All here are pretty well, you can tell John that Sam has exchanged the old cow for that horse that Sam has heard speak of and John Collinge has been breaking it in, and tell John that John Collinge says he thinks it will soon be ready for ME to ride. It will just do for a ladies' pony. Ask John if he does not think it will look a great deal better with me upon its back than with him.

The weather is so fine at present, it is a delightful change from the bad weather we have had. Sam is so industrious you cannot think, he often gets up at five o' clock in a morning and goes into the mill ...

Your affectionate sister,

Mary Fielden . . ."

It is not so hard to imagine Mary with her new pony. No doubt her brother's friend had designs on it also, as she seems to be rubbing it in that she had 'bested' him in getting the pony! No doubt she kept it in the old stable block we passed on the other side of the canal.

Not all of Mary's letters brought news so cheerful. Disease and death were constant companions in an age where sickness was rampant, and medical knowledge and hygiene virtually nonexistent. In the 1830s the average life expectancy was far lower than it is today. Infant mortality in particular was high, a fact which no doubt explains the tendency of early Victorians to beget large families. The Fielden children at Dawson Weir were luckier than many of their class, for all seven of them managed to grow up and take their place as adults; though their mother, Ann, died in 1831 when Mary was 14 (her youngest sister Ellen was only 2). No doubt she was, like many nineteenth century women, worn out with bearing children.

In 1834 John Fielden took a second wife, Elizabeth Dearden of the 'Haugh' in Halifax. Whether or not Mary liked her new stepmother is unknown, yet by 1836 she was attending yet another funeral, within months of getting her pony...

"Dawson Weir

September 18th 1836.

My Dear John

You will be very surprised and very sorry to hear that we have had another of our friends taken from us.... about half past twelve this morning my Aunt Lacy of Stoodley departed this life after an illness of more than a week . . . she had a paralytic stroke which deprived her of the use of her right side ... We saw my aunt yesterday, she appeared very ill and much altered in appearance since we had seen her the week before. My uncle Lacy is of course very much distressed, but wears the affliction as well as can be expected. Someone will write to you again, either tomorrow or Tuesday and inform you about your mourning."

Betty Lacy (nee Fielden), wife of Henry Lacy of Stoodley Hall, died at Stoodley Hall aged 60. She is buried in the Old Churchyard at Todmorden. The grim theme of sickness and death continues in other letters. Earlier in the same year Mary expressed concern over the condition of her mother, (actually her stepmother, Elizabeth Dearden), who had dropsy in the chest and was seriously ill. (Nowadays this would be diagnosed as severe bronchitis or pneumonia). The prescribed treatment for such a condition seems, to modern eyes, more severe than the condition itself:

"Doctor Henny told her that she required the greatest care, attention and quiet, that she has not to walk much, not to go down stairs and not to go uphill. He ordered her a blister and some medicine. She has a blister put on every other morning and lets it remain on for 24 hours when she has it taken off and some healing ointment put on . . . She is at the Haugh and will remain there, I suppose, until she is better. She went last Friday ... I do not wish you to tell anyone what my mother's complaint is as she might not much like it, and it may be better not .. .

Your attached sister,

Mary Fielden."

A 'blister' or 'blister plaster' was used medically in those days to raise blisters as a counter irritant, it was composed of a compound of Spanish Fly (cantharis), beeswax, resin and lard, to make an externally applied medication. Because of (or more likely despite!) this treatment, Mary's stepmother recovered, to die two years after her husband, in October 1851, at the age of 63.

By this time Mary Fielden had married in the January of the same year, at the age of 34. Her husband was John Morgan Cobbett, son of William Cobbett, the famous radical journalist and author, who was her father's close friend and fellow M.P. John Morgan Cobbett had attended her father's funeral in June 1849, and had no doubt consoled the grieving daughter. Certainly the Fieldens were no strangers to the Cobbetts, for in one of her letters in 1840 Mary states that "Mr. James and Mr. Richard Cobbett came here on Saturday night... Mr. Richard went back to Manchester this morning, but Mr. James is still here. . . " These were presumably John Morgan Cobbett's brothers. Perhaps Mary's husband to be was the 'John' who was at school with her brother, the one she 'bested' over the pony. Who knows? Whatever the case may have been, they were certainly well acquainted.

After her wedding Mary left Todmorden and went to live with her husband at Farnham, Surrey (where there is now a Cobbett Museum). She bore him two sons, John Fielden Cobbett and William Cobbett and a daughter, Mary. Her husband died in 1877 and is buried at Farnham.

We will leave Mary Fielden with an amusing but also sadly revealing anecdote. As Ian Dewhirst has pointed out in his History of Keighley, emigration caused by hardship, poverty and the threat of the workhouse was a common phenomenon in the 1840s and '50s. Even the penniless could escape abroad for a consideration; it was so easy, in fact, that men would often ship out for California or the Cape of Good Hope, abandoning wife and children to the workhouse:

"Dawson Weir.

March 23rd 1840.

to John Fielden M.P.

17 Panton Square

Westminster.

My Dear Father, have you heard that William Greenwood the grocer (who came to chapel) went along with Thomas Dawson to America. It is said that he is gone out of the way of his creditors because he is in debt, but I have heard that they can pay their debts, if they receive what is owing to them. He has left his wife and family behind, and is gone intending to buy a piece of land, and if he thinks he can do well he will either send for or fetch his family . . ."

We can only speculate as to whether or not he ever did. Perhaps there is someone now living in some part of the United States who can supply the answer?

We have now reached the end of Section 2. If you parked your car at the start of Section 1, you will find it just five minutes walk away. Simply turn left for Todmorden Town Centre. If, however, your car is at the beginning of Section 2, you will have to follow the Burnley Road all the way up to Cornholme (catch the Burnley bus.)

Copyright Jim Jarratt.

2006 First Published by Smith Settle 1989

Prosperity and growth however, were not the only new developments at the court of King Cotton. There were other, less agreeable 'innovations' like bad housing and sanitation, grinding poverty, child labour, dangerous working conditions, and, most significantly of all, unbearably long hours. "Overwork," wrote Leon Faucher in 1884, "is a disease which Lancashire has inflicted upon England, and which England in turn has inflicted upon Europe."

It was in this context that the name of Fielden was to become universally esteemed, and to earn a fame far more enduring than that of mere charitable mill magnates, as we shall see. The Fieldens saw the benefits that might be derived from the factory system, but, unlike most of their class, they were painfully aware of the evils it created, and took steps not only towards easing the lot of the working man, but also towards his political emancipation, as we shall soon discover.

The next section of the Fielden Trail leads to Todmorden Edge. After meeting the path coming up from Robin Wood Mill, continue onwards and slightly upwards, contouring round the hillside. Soon there are good views down the valley towards Todmorden, with Centre Vale Park and the Mons spinning mill in the foreground.(AUTHORS NOTE Since demolished!) Mons is a much later mill than Fielden's at Robin Wood, and was built on The Holme, a large open space where fairs and circuses were formerly held. Opposite the remains of Royd House, which is now just a pile of stones overgrown with elder trees, join an ascending track in a gully (passing yet another ruin) which soon arrives at a rusty old gate facing West End on the hillside, to the right of another farm, Dike Green. Here the alternative route from New Towneley is met with. If anybody decided to miss Robin Wood Mill from the itinerary and take the short cut, they will be waiting for you here. Now turn left (you will have to climb over the wooden gate) and follow a green track past the head of Scaitcliffe Clough. At Flail Croft nearby, lived (in 1714) Samuel Fielden, brother of Nicholas of Edge End, and John of Todmorden Hall, both of whom we will encounter later. Continue onwards until a wall and wooden gate are joined (on left). Pass through this gate, and be careful when you shut it, as when I did so I was miles away in thought and did not see the eye level barbed wire which made a neat little cut on my forehead! Beyond a stone in the wall on which is carved the letters I M bear left across the fields to enter the lane leading to Todmorden Edge.

Todmorden Edge

If Nonconformism had shrines then Todmorden Edge would certainly be one of them, for it has associations with both the early Quakers and the early Methodists. Quaker meetings were held at Todmorden Edge Farm and, as at Shore, there is a 'Quaker Pasture'. Early Quakers were persecuted, and Todmorden Edge has seen its share of that. Henry Crabtree, who was curate of Todmorden in the 1680s, viewed the Friends with great distaste. With Simeon Smith, his servant, he surprised a number of Quakers from Walsden and Todmorden when met together at the house of Daniel Sutcliffe, at Rodhill Hey on May 3rd 1684. A fine of five shillings was imposed on each person present. As the fines were not paid, distraints were made on their goods. A month later, a meeting in Henry Kailey's house at Todmorden Edge was similarly disturbed and goods to the value of 20 pounds, an ark of oatmeal, and a pack of wool were taken.

Todmorden must have been noted for the number of Friends, for when those who declined to pay for repairs to the church and school at Rochdale were summoned by the Rochdale Churchwardens, it was stated that the majority of the offenders came from Todmorden, where Quakers were "both numerous and troublesome". Fortunately for the Fieldens and others of their faith 1689 saw the passing of the Toleration Act, which enabled Quakers to register their meeting houses officially for the first time.

In the wake of the Quakers came the Methodists. On 1st May 1747, John Wesley preached

at Shore at midday; then later, at Todmorden Edge Farm, he called "a serious people to

repent and believe in the Gospel". The following year, on October 18th 1748, the

first recorded quarterly meeting ever held in Methodism took place at Chapel House,

Todmorden Edge, under the chairmanship of that noted religious firebrand William

Grimshaw (who was curate of Todmorden before his more famous association with

Haworth). Methodism obtained many converts, and the Friend's Meeting House at Todmorden Edge, along with a Meeting House and a Baptist Chapel at Rodhill End, were sold to the Wesleyans.

The Fieldens, unlike many of their Quaker brethren, were not converted to Methodism. They remained Quakers, but for all that the Methodists were to play an important part in the establishment of Unitarianism in Todmorden, with which the Fieldens were actively

involved.

From Todmorden Edge the Fielden Trail moves on to Edge End, the home of Todmorden's first industrial entrepreneur, and father of 'Honest John' Fielden, Joshua Fielden of Edge End. As we leave Todmorden Edge with its Wesleyan associations it is perhaps worth bearing in mind that John Wesley, for all his goodness and unwavering faith, went so far as to recommend child labour as a "means of preventing youthful vice". John Fielden, who was born 36 years later in 1784, would hardly have agreed with such a sentiment.

On meeting the Calderdale Way by the stables at Todmorden Edge Farm, bear right, following the concreted farm road past a white gate to where it meets tarmac at Parkin Lane. From here the route continues without difficulty (following the Calderdale Way) to......

Edge End Farm

At Edge End we come to an important chapter in the Fielden story. Here is the scene of the Fielden's transition from farming and wool to industry and cotton. This low, embattled stone farmhouse hugging the hillside was where the Industrial Revolution in Todmorden was born. The initiator of the chain of events which was so greatly to transform the fortunes of both the Fieldens and those around them was Joshua Fielden, 'Honest John's' father. Joshua Fielden was not the first of that name, nor would he be the last. His second son was called Joshua, and he was to have a grandson and a great grandson of the same name. As if that was not confusing enough, we also find that his father, grandfather and great grandfather were also called Joshua! Because of this I have found it necessary to number all these 'Joshuas' in the hope of lending at least a little clarity to a confusing and misleading situation.

Back at Hartley Royd we discussed Abraham Fielden of Inchfield who married Elizabeth

Fielden of Bottomley in the early 17th century. Their third son, Joshua Fielden of

Bottomley, although not the first Fielden to bear that name, was certainly the first Joshua in his

line, so for that reason I have referred to him as Joshua (I). From him the Joshua Fieldens of Bottomley and Edge End run as follows:

JOSHUA FIELDEN (I) of Bottomley Quaker. Received Bottomley from brother John of Hartley Royd. Died 1693.

JOSHUA FIELDEN (II) of Bottomley. Died 27th February 1715.

JOSHUA FIELDEN (III) of Edge End. Born Bottomley. Died at Dobroyd. (1701....1781)

JOSHUA FIELDEN (IV) of Edge End and later Waterside.

(1748...1811).

From this we can see that 'Honest John's' father was the fourth successive Joshua in his line. Joshua Fielden (IV) was a Quaker like his forebears, and who lived in "a bleak, pious fashion" at Edge End Farm. His uncle Abraham (1704...1779) had inherited property at Todmorden Hall (this is a connection we will explore later) and was actively involved in the domestic textile industry. Joshua too, like most of the farmers around him, was involved in the production of woollen cloth, which was the traditional occupation of the whole district. By the mid 18th century the domestic system of cloth production had reached the height of its importance. Originally the farmer weaver simply produced his cloth at home and carried it to market (a cloth hall had been established as early as 1550 by the Waterhouse family of Shibden). Soon however, the business diversified and expanded: weavers collected into small settlements, the weaving hamlets linked by causeys and packhorse ways; while local merchants often acted as middlemen, selling raw wool to the weavers and buying back the finished cloth. As a result of this, in the 17th and early 18th centuries prosperous clothiers' houses began to appear, many of them with a "takkin' in shop" alongside. By the mid 17th century Halifax had its own cloth hall, but did not completely supersede the Heptonstall one until the Halifax Piece Hall was opened in 1779.